Chapter 17

Eddy and Teresita, Catholics of the Left

The great challenge to Castro in the initial period of the revolution was the widespread fear of Communism by the middle class. This Cold War mentality was amplified through the influence of the Cuban Church.

In Place, through the memories of Eduardo, “Eddy” Casas and multiple secondary sources, examines the roots of the stand-off between Castro and the Church.

Eduardo Casas knew of Fidel Castro, a talented organizer of dissident action, who was a year ahead of him in the University of Havana Law program. They had attended the rival Catholic schools in the capital: the former de la Salle, run by the Christian Brothers and the latter the Spanish Jesuit-run Belen. The echoes of Republican and Falangist attitudes towards politics would surface among the generation of students that were taught at these elite schools for boys.

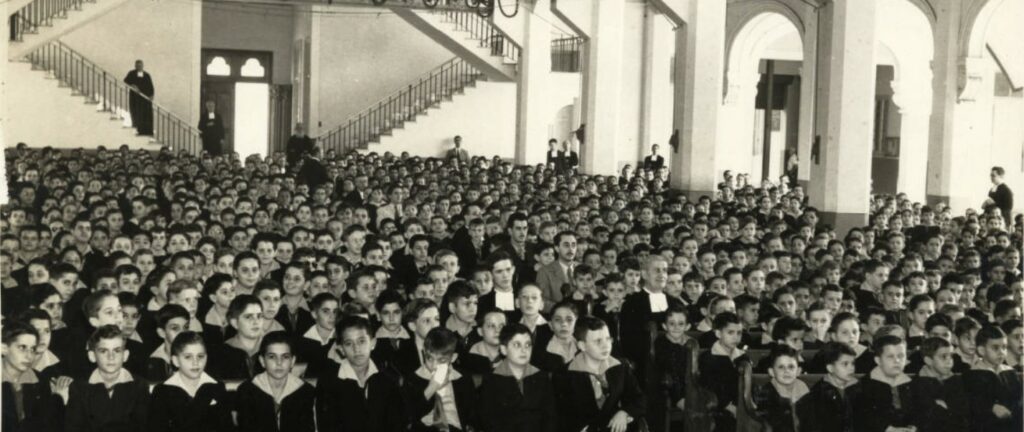

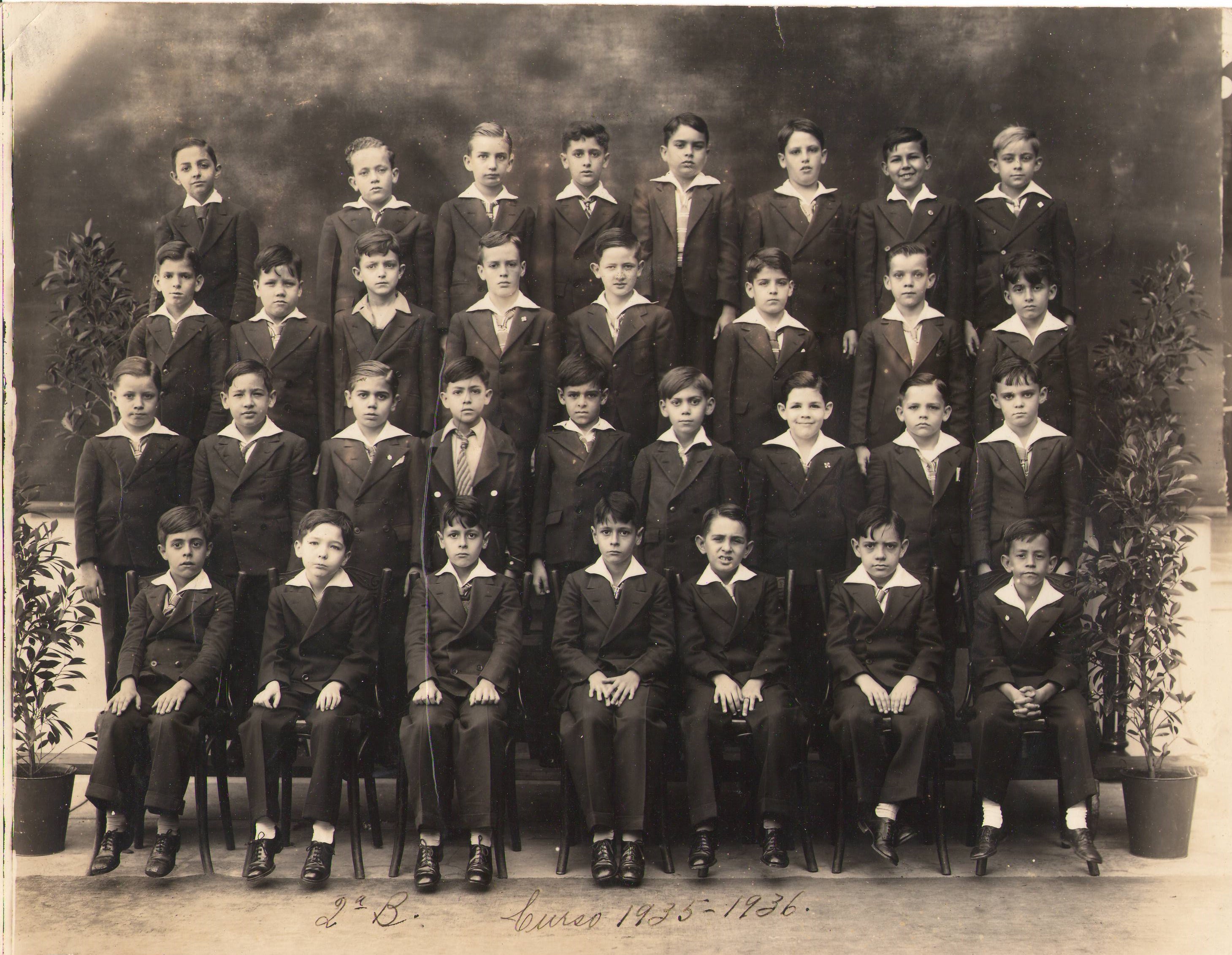

(Eddy Casas second row, third from right) By 1925 the new Colegio de La Salle building in El Vedado was ready for students. Enrolled in

1933, Eddy Casas’ academic cohorts were Teresita’s cousins, the sons of Agustín Batista and

Viriato Gutierrez whose homes bordered the school. Agustín Batista financed the mortgage for

this Catholic primary and secondary school for boys, and would later put up much of the money

for the founding of the first national Catholic university, Santo Tomas de Villanueva

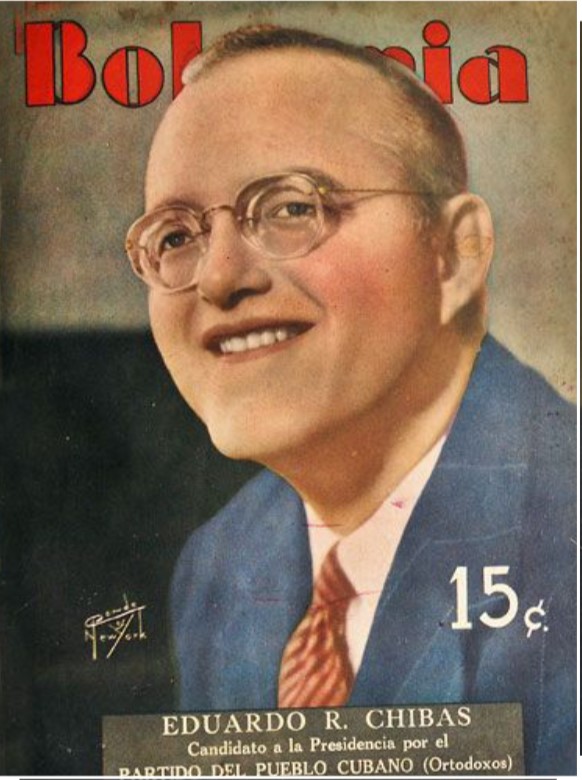

In anticipation of the 1952 election, the Partido Ortodoxo promoted its leader Eduardo Chibás as someone who could “sweep away” corruption, terrorism, American domination and poverty.

However, before the election could take place, Batista obtained approval for a military coup from the American Ambassador by accusing Chibás and members of his party of being Communists.

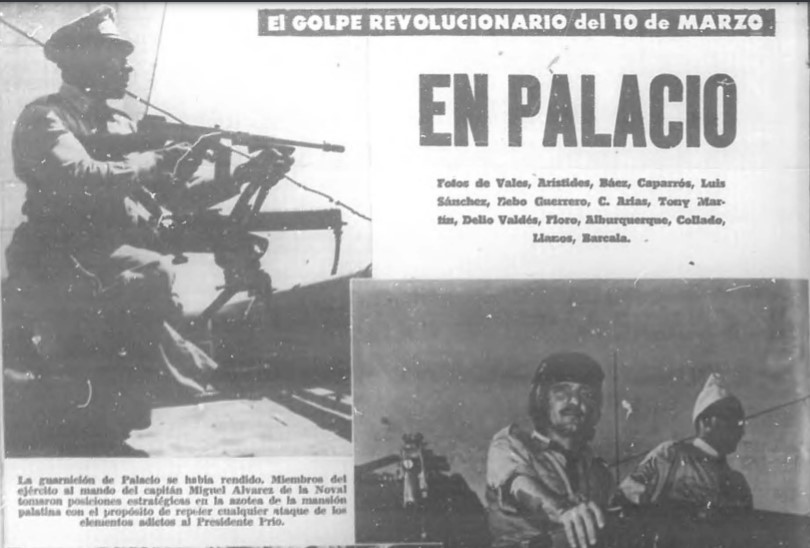

Early in the morning of March 10, as the last stragglers of carnival celebrations were going home, tanks rolled up to the Presidential Palace. The following seven years would be marked by brutal suppression of any opposition towards Batista’s brutal regime.

The short-circuiting of the election enraged Castro, a member of the Partido Ortodoxo. In reaction, he led 60 revolutionaries in an attack on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago on July 26th of that year. They were overpowered, many were tortured and killed, and Castro was jailed.

The resistance went underground in Havana and sales of bonds to support the “Movimiento 26 de Julio” (26th of July Movement) skyrocketed

Eddy was with majority of the population who favored bringing down a dictator and in sympathy with those risking their lives by selling bonds to support the armed insurgency.

To raise money for the cause, they sold bonds, but if they were caught doing this, the police arrested, tortured and often killed them. I had friends who sold bonds and tried to sell to me and I had a friend, a fellow member of the Juventud Católica that they killed, they tortured and killed him. I saw the corpse covered with blood, they left it on the street where his brothers picked him up and buried him. Eduardo Casas

After obtaining his law degree in 1950, Eduardo received a one-year scholarship from the Alliance Francaise to train as a French teacher in Paris. On his return to Havana, he enrolled in Psychology, a field in which he could amalgamate most of his previous studies. This prolonged period at the University of Havana brought him into contact with individuals working with student organizations to respond to the political situation of the fifties.

Specifically, Eduardo became involved with the debates over the role of culture, notably film the transformation of society. In Place outlines the Church’s attempts to use film clubs to instruct on moral issues through its lay organization, Acción Católica. This initiative was set in the larger debate among intellectuals on the need for a home-grown film movement to counter Hollywood’s sway and correct Cubans’ colonial mentality. Both the heady discussions and the movement to take film to the masses were groundwork for Cuba’s celebrated cinema of the 1960s.

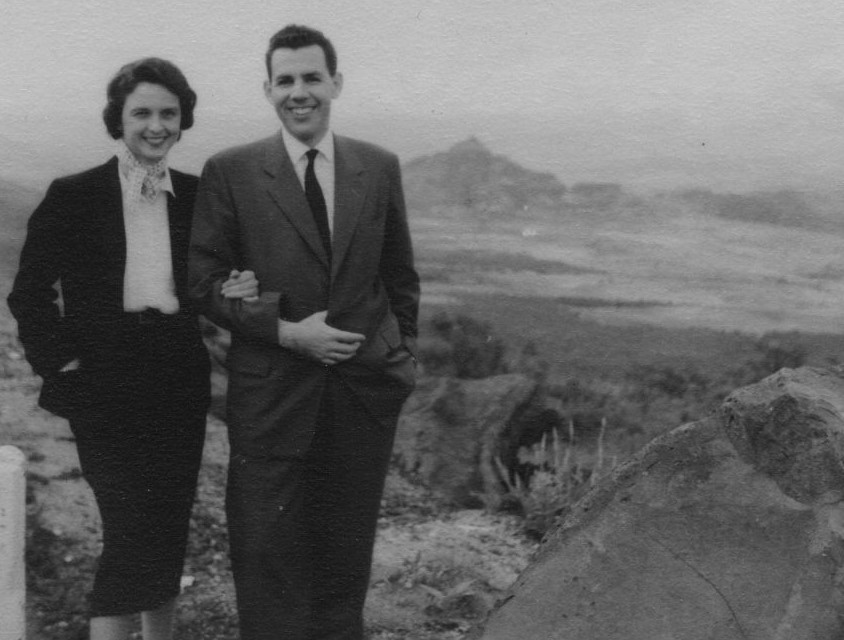

Avoiding the specific political or religious agendas in the air, Eddy Casas, in his role guiding cine club discussion at Juventud de la Acción Católica, asked members to consider the film from the standpoint of moral conscience, universal principles and humanist values. His ability to lead discussion, knowledge and sensitivity drew the admiration of Teresita Batista. They married in 1956.

In contrast to the activity of the Batista women who expressed loyalty to the Church through its education and charity networks, at the College of New Rochelle Teresita learned that the Catholic faith could be integrated with critical inquiry and social activism. Far from the traditional Cuban religious environment, she grew familiar with the social doctrine and call for action that had been published by the Church earlier in the century. To the irritation of her atheist mother, Teresita came back from the North more religious than when she set out.

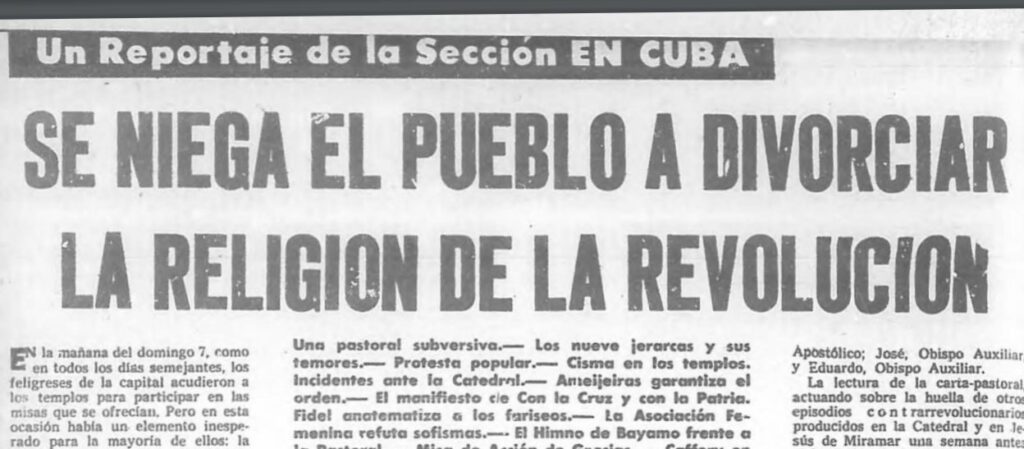

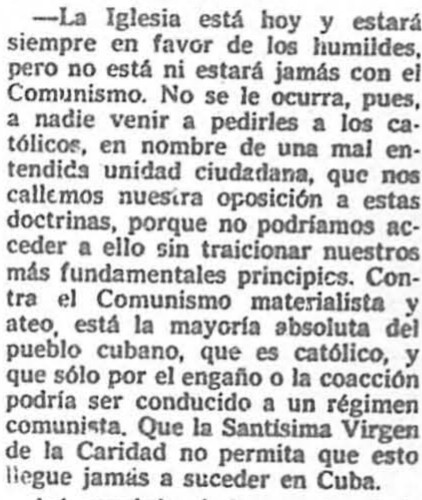

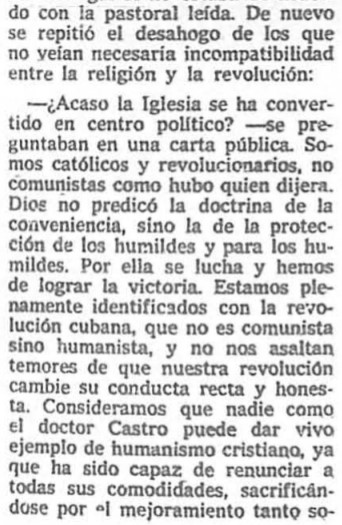

Castro, before he had worked out an ideological framework for his government, recognized that the Church held the power to protect and organize opposition. To counter this he revived memories of the Church as an instrument of colonialism. Denouncing it for thwarting the self-determination of a people, he invoked its checkered past on the island. For their part, Church leaders provoked panic with declarations that Castro was a Communist.

The rhetoric of fear and prejudice was self-fulfilling. Castro and the Church polarized a confused population into two camps. The Church gave the middle class a moral imperative to reject the revolution, a move that perversely resulted in the radicalization of its course and the consolidation of Fidel’s power. The firmly drawn battle lines blurred what in reality had been a complex and nuanced history of Catholicism as a moral and intellectual force for personal development among the members of the Cuban middle class.

The political corruption and social injustices of their era forced the members of the generation of the 1950s to carefully define their political attitudes. Eddy and Teresita, through their Catholic lay organizations, rejected religious proselytizing in favor of promoting a social conscience in keeping with a liberal Catholic tradition. After the revolution, like many Cuban Catholics, they struggled to find a position within what many saw as oppositional principles of Socialism and Catholicism.

Chapter 18

Revolution, Education and the Family

Like other events of my parent’s early-married life, my arrival on January 3rd 1959 as the first revolutionary troops marched into Havana, was in step with historic events on the island:

They were married in June 1956, six months before Castro’s small guerrilla army ran their yacht, Granma, aground on the southwestern point of Oriente province.

A year later, my father was permitted to defend his doctoral thesis despite the fact that the University of Havana had been temporarily closed-down after a student attack on the Presidential Palace.

My birth coincided with the entry of the first revolutionary troops into Havana.

Eduardo obtained a Master’s degree, this time in Psychology, from the University of Santo Tomás Villanueva and a Doctorate in Philosophy from Havana University. Unfortunately, not long after beginning to teach at the former, it was closed by the new Revolutionary Government as part of the abolition of all private educational institutions.

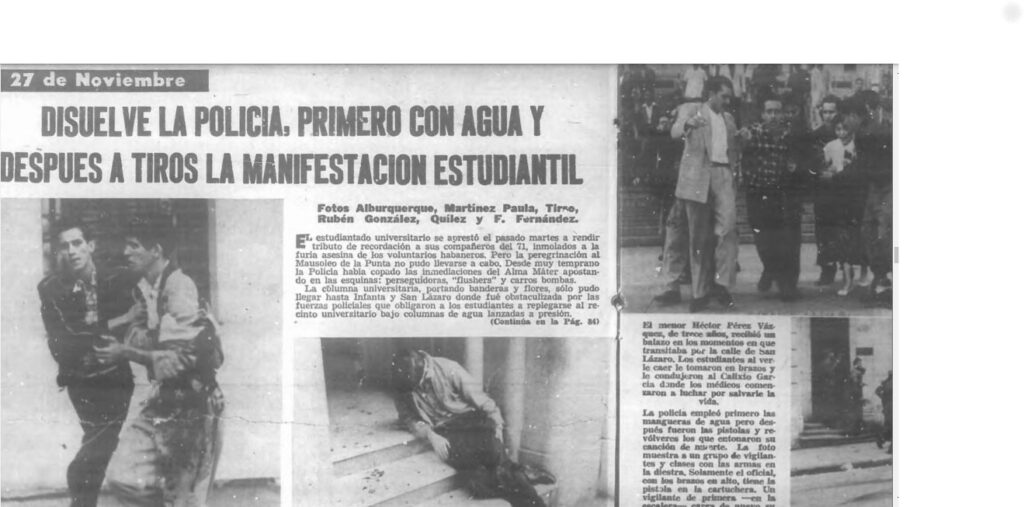

See Bohemia article: Fifth Column in Catholic Schools: “Existe un Quinta Columna in los Colegios Catolicos”, Bohemia, 27 November 1960 p26

Despite this unpromising start, the professional lives of both would pick-up after Castro’s victory. Using the money from expropriated property and the services of professionals who like them “stayed behind,” the Revolutionary Government kick-started a social transformation of unprecedented pace and scale. As the exodus of the middle class began to gain momentum, Castro quickly put to work the expertise of those professionals who remained. Among those were Eddy and Teresita.

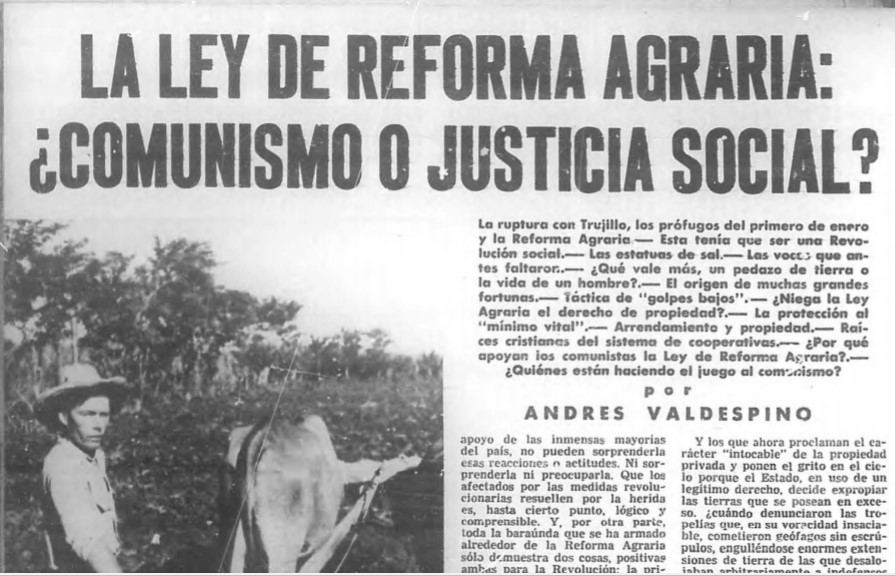

For many, the details of Castro’s 1959 agrarian reform plan such as the organization of “collectives” confirmed fears that he was a Communist. Divisions temporarily covered-over by the euphoria over Batista’s fall, dramatically widened. President Urrutia, appointed in January, was fired by Castro in July. He had wanted to apply brakes to the reforms.

On July 5, 1960 all business and commercial property in Cuba was nationalized. Three months later, the United States imposed an embargo prohibiting all exports to the island.

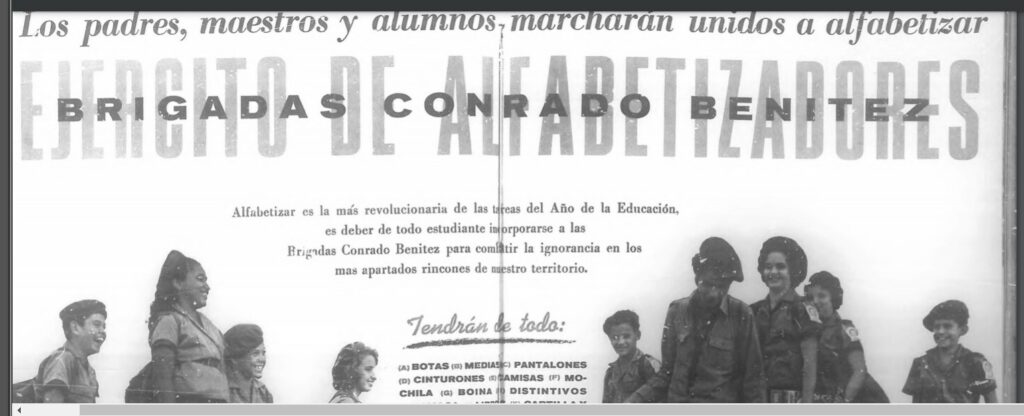

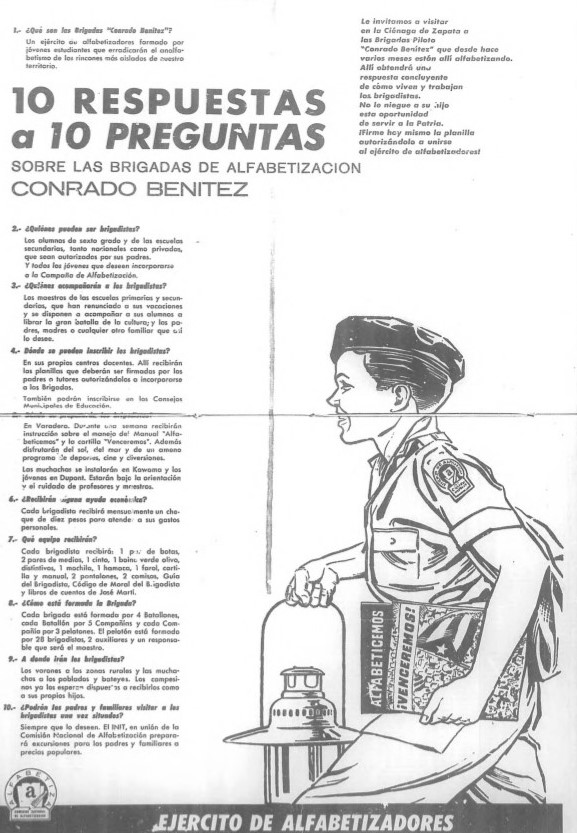

To counter-act the fall-out over this, Castro’s announced that 1961, the “Year of Education” would feature a campaign to wipe-out illiteracy on the island. The initiative gave credibility to a revolution that had collected many critics inside and outside the country.

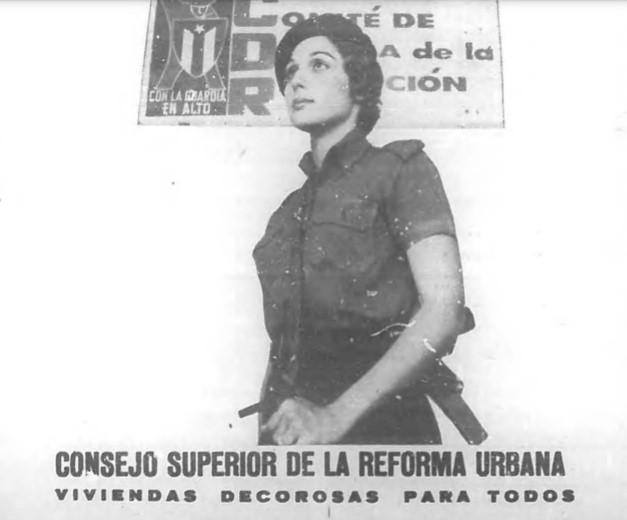

The government used the homes of those who had fled the country to house and educate the underprivileged. Rich and poor, black and white, country and city: people were to be shuffled according to an urban reform plan for an egalitarian city.

A new bureaucracy was set-up In the wake of a radical re-structuring of the school system. In this moment, Eduardo’s research expertise was newly valued in the Ministry of Education. It could offer empirical evidence to optimize the revolution’s educational reach.

Prior to 1959, Eduardo had worked in a clinic within the Ministry of Public Health.

There, a cross disciplinary team would analyze the psychological problems of the children who came to the institution. With the revolution, the clinic and its model of care based on service to individual children disappeared. The revolution prioritized the needs of the system above those of specific individuals.

At the Ministry of Education, Eduardo’s work focused on supporting the work of the young women who took care of the children living in the “casas de internados”, homes for young, out of town students or orphans. As these children’s mental and intellectual development were not on par with those living with their families, he worked with the women caregivers to enrich interaction and services within the homes.

Eddy and Teresita started their own family in the midst of a revolution. They were witness to the sudden leave-taking of many other young families during the early days of Castro’s power and then, several years later, to parents swept up in Operation Peter Pan, a panic-driven airlift of children that was, in part, triggered by counter-revolutionary messages.

The 1960 literacy campaign recruited youth (sixth graders and up) to teach reading and writing to people in the countryside. In the eyes of many parents, this was part of a strategy to subvert their moral influence and to force them to give-up their children to the mind control of a totalitarian state. Behind the alarm was an objective reality: In its mission to re-make society a revolutionary state sets out to rival the family as the formative influence on its young citizens.

Many Cubans who left the country shortly after the revolution never abandoned hope of returning and so entered into an un-ending state of exile. By extension their children, in contrast to those back on the island who identified with a future promised by the revolution, were caught up in the memorializing their (home-country) family past. This generational task is examined through the writings of Cuban American writers Gustavo Perez Firmat and Carlos Eire for both its burdens and strengths.

Chapter 19

Art Under the Shadow of the Missiles

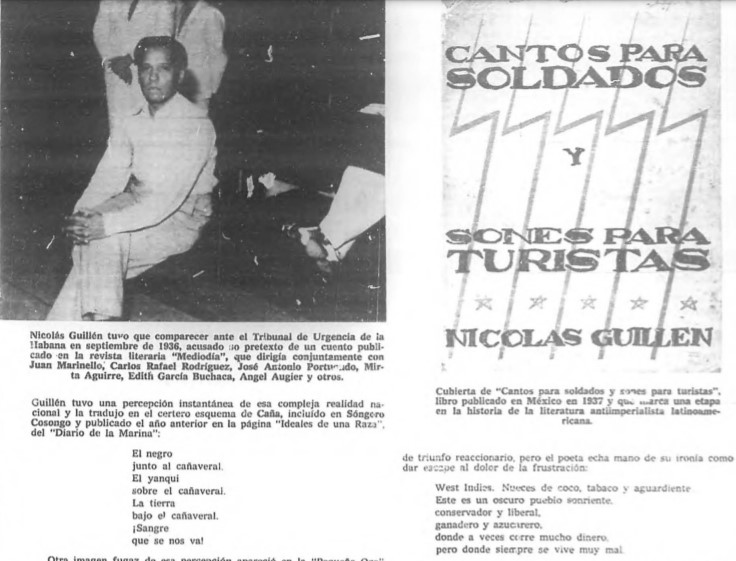

The Cuban revolution set out to recover a nationalist history long obscured by the island’s colonial condition. Led by an experimental impulse and dedication to social development, there was a search within each artistic medium for a formal language with which to express the nascent Cuban consciousness. For many, the route to the future lay in a fresh return to the past, to folklore, and to the repressed black heritage.

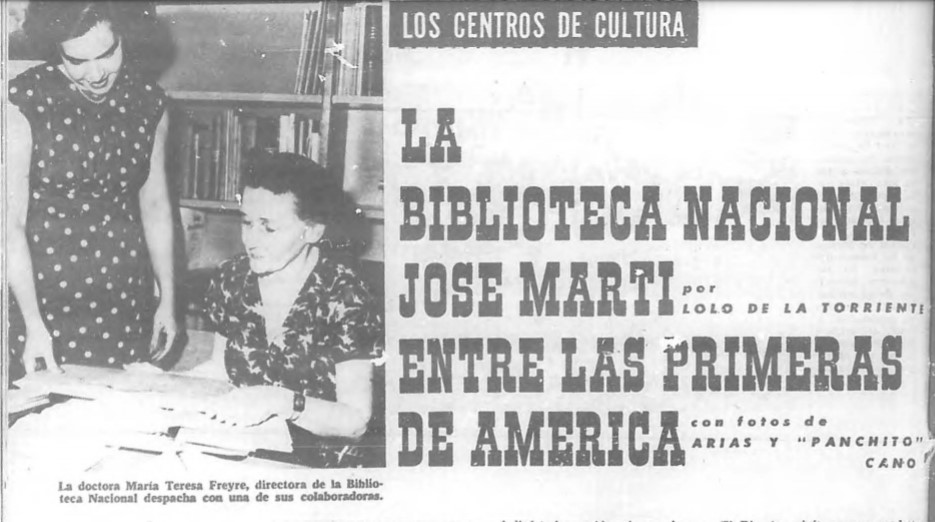

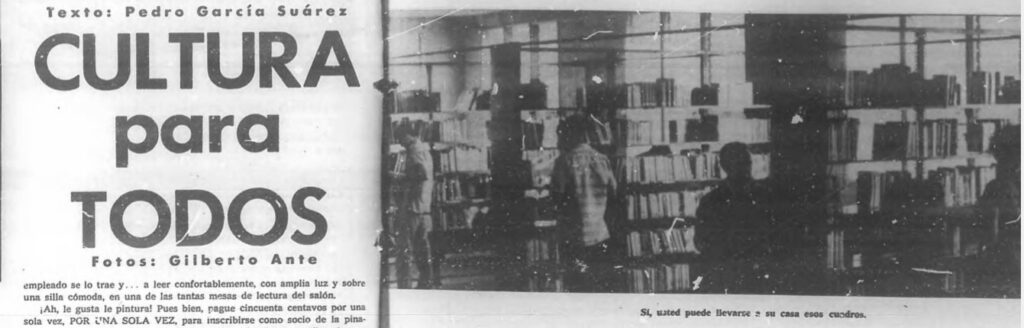

The ark of Cuban heritage was to be the national library, Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba Jose Marti.

Teresita obtained her Library Science degree at the University of Havana so that she could work under Maria Teresa Freyre. She shared in the latter’s vision for an open culture founded on literacy, access to books and knowledge of Cuban heritage.

During her period at the National Library, Teresita was the principal author of a catalogue of Cuban periodicals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries based on the José Martí National Library’s holdings. These newspapers and magazines, because their runs were often brief or interrupted due frequent periods of censorship, were a highly ephemeral part of the historical record. Teresita’s 1965 bibliographic work continues to be an important source for understanding the existence and scope of colonial-era Cuban periodicals.

For those in the creative class who had stayed behind, the question was: How could artistic expression advance the revolution’s goals?

However, the experimental impulse of the 1960’s was increasingly at issue with officials. Was freedom of expression guaranteed by the revolution?

The debate’s defining moment was Castro’s “Words to the Intellectuals” speech. delivered in July of 1961 at the National Library, Castro’s ominous guideline for the sounded a warning: “Dentro de la Revolución todo; contra la Revolución nada.”(Within the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing.”)

In the United States, the ideals of the revolution attracted many followers who began to watch developments with interest. From the New York editorial office of The Catholic Worker, Dorothy Day wrote to her readers about the situation in Cuba, adding, “We have been invited to visit by a young woman who works in the National Library.”

Day had been carefully weighing the positive with the negative trends. The troubling reports of the persecution of the Church, its priests and the faithful came in alongside those of ambitious

national programs to eliminate hunger, racism, homelessness, illiteracy and other root sources of poverty. Day looked to Cuba for new grass-roots models for creating social equity. ‘There is a Christian communism and a Christian capitalism… We believe in farming communes and cooperatives and will be happy to see how they work out in Cuba.’

Teresita Batista, the young woman who had extended the invitation to Day, received an

acceptance the following year. As Eduardo Casas explains, for them, the work of the elderly

woman reflected the synthesis of their liberal Catholic values with the spirit of social reform at

the heart of the revolution.

The view of the revolution was increasingly tinged with alarm. In March 1961, a CIA backed and trained army of exiles had landed at the Bay of Pigs where they were summarily defeated by Castro’s army. Within Cuba, the invasion fanned widespread fear of further counter-revolutionary violence.

Day’s visit coincided with the second event that determined the political course of the island. She arrived in October 1962 on the eve of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a development that caused authorities to revoke her journalists’ pass and cancel all direct flights between the island and the U.S. In discussions with Day, her hosts Eddy and Teresita, discussed the rapid escalation of hostility. In their view, Castro’s denouncement of Yankee imperialism and American accusations of his Communism was an interdependent dynamic.

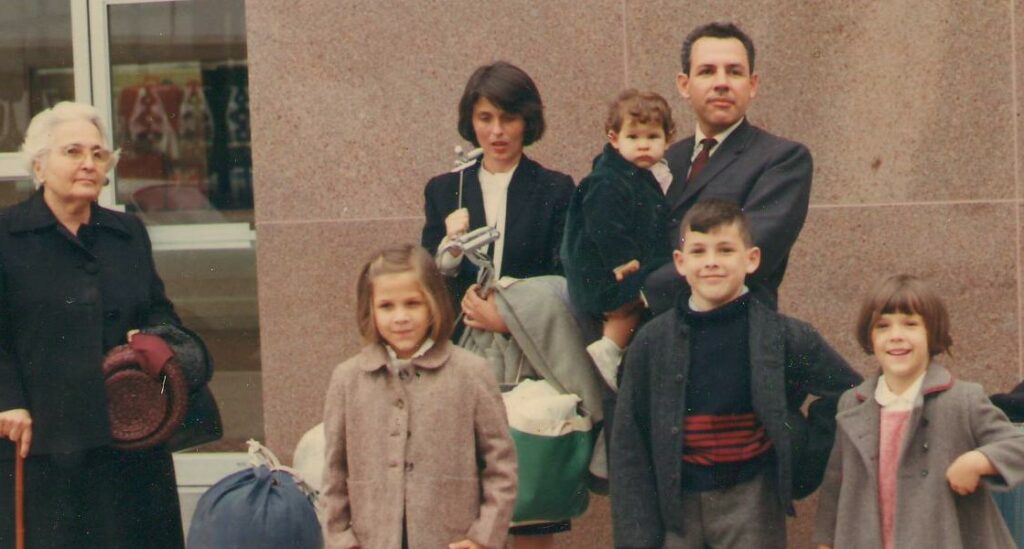

Under the circumstances, it was fortunate that the demands of their growing family helped to

keep the young couple focused on their day-to-day concerns of school, diapers, and meals.

Spurred by the imminent arrival of a third child, late in 1960, they had bought their first family

home. Located on 28th Street between Third and Fifth Avenues, it was just around the corner

from the Church of Santa Rita de Casia in Miramar.

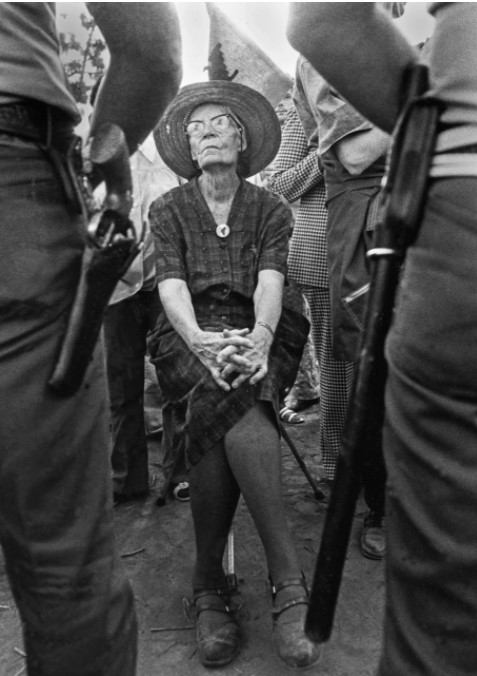

The year 1960 had seen the emergence of the counter-revolution that took the form of economic sabotage through bombings inside Havana and, as well, air hits to such economic targets as cane fields and oil refineries. The Comité de Defensa de la Revolución, driven by both fear and opportunism, was the government’s response to the socio-political circumstances of the period. It drew on the desire of those who had profited from the revolution to protect it and advance their lot under the new regime.

In creating the foundation for a new society, the government needed the solidarity of a population that felt involved in a moral battle. This struggle was not only about bringing about domestic reforms but defending these, and the revolution, against enemies. According to the government, the two roles, activist and a vigilante, were essential for one to be part of the revolution.

Members of the CDR, who were most often women, kept detailed records of their neighbors, so extending the vigilance of the state deep into the private lives of its citizens. The notes on Eduardo and Teresita, for example, were not only to expose misdemeanors but also to create a working profile of their political reliability. The visit of an American during the missile crisis would have been of singular interest. With the pretext of defense against its enemies and exploiting individuals’ desire for advantage, the government began to extend itself into all aspects of life.

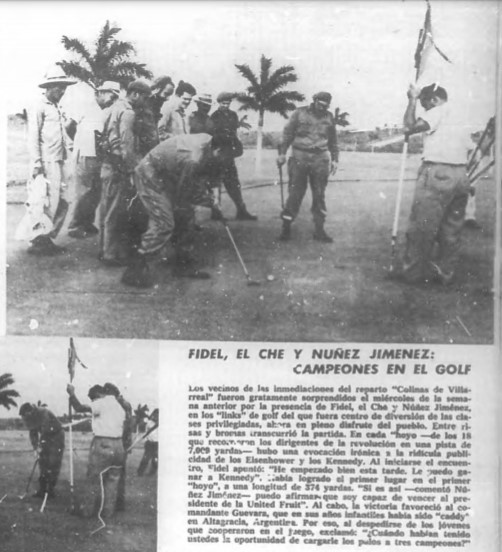

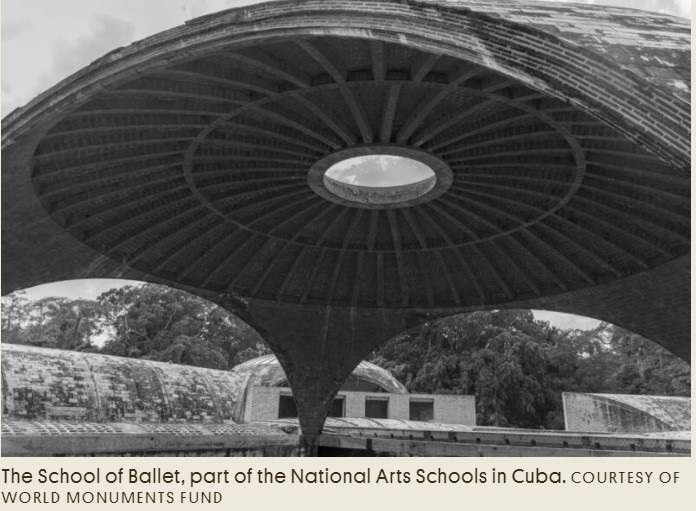

Signaling the importance of education, a complex of buildings for professional training in the arts was ordered constructed shortly after the revolution. Just as ousted President Batista’s army barracks was renamed Ciudad Libertad, and transformed into an educational center, the neighboring Country Club that had served as meeting ground for the elites, was renamed Cubanacán and chosen as the site for the arts schools.

Fidel had ordered the most cutting-edge architecture and tapped Ricardo Porro to lead the project. From among the series of buildings to be constructed, Porro chose the Visual Arts and Dance schools and recruited two Italian architects Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti to carry-out the others.

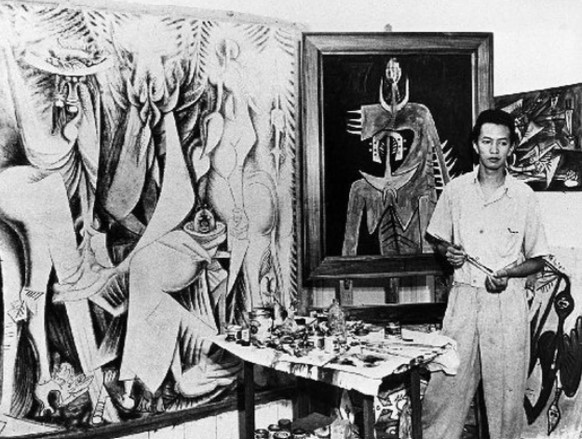

In conceiving of the plan for the two schools, Porro looked to the spirit of Afro-Cuban culture.

He felt this to be an appropriate reflection of that historical moment when the Catholic elite was fleeing the country so making way for the ascendance of the other, formerly repressed half of the national patrimony. The animism of Santeria, already the source of inspiration for such

modernist artists as Wilfredo Lam, became Porro’s essential point of reference.

The architect took the elaborate rhythmic structures and organic forms of Afro-Cuban art

translating these materially in compositions of brick hand-constructed vaults. In speaking of the School of Visual Arts he explains, that above all, he meant his buildings to be an echo of

primordial creative energy.

I conceived of the building as a manifestation of Eros… the point of

departure of my School could have been Gaia, the Greek goddess of fertility, and equally Ochun. The theme was Eros, and of course it was the Eros that we inherited from Africa.

While Porro insists that he was breaking from the project of modernist colonial architecture, critic Eduardo Rodriguez puts his design for the schools within the trajectory initiated with the cultural nationalism debates of the 1920’s.

The leading twentieth century Cuban architect, Leonardo Morales, argued for the Cuban regionalist adaptation of the international design language. Eugenio Batista, the most accomplished exponent of this trend summarized the national architectural vernacular in the three P’s –puerta, persiana, portal. (portal or portico/veranda, louvers/persian blinds, and courtyard/patio).

Rodriguez argues that the Cuban regionalist movement encompassed a great formal diversity nevertheless it was united in the quest for a creative balance of varying influences. Each construction was a reconciliation of the seemingly opposite categories: modernity and tradition, the universal and local, international vanguardism and national identity. The height of innovation within this approach had been in the 1940’s and 1950’s in the form of domestic architecture for Havana’s suburbs.

In this context, Ricardo Porro was in fact adhering to the principles that had been in

development for the past four decades but applying them to another scale and function of building. Instead of being concerned with home-building he was creating a monument to a conception of a national culture in a highly original way. His buildings were made to evoke and celebrate nothing less than the visceral sensation, the gut-feeling of a revolution.

In Place discusses the initial embrace and then rejection of the avant garde architecture of Cubanacan by the revolutionary government. The buildings, like many architectural treasures within Havana slowly decayed contributing to the city’s other-worldly atmosphere.

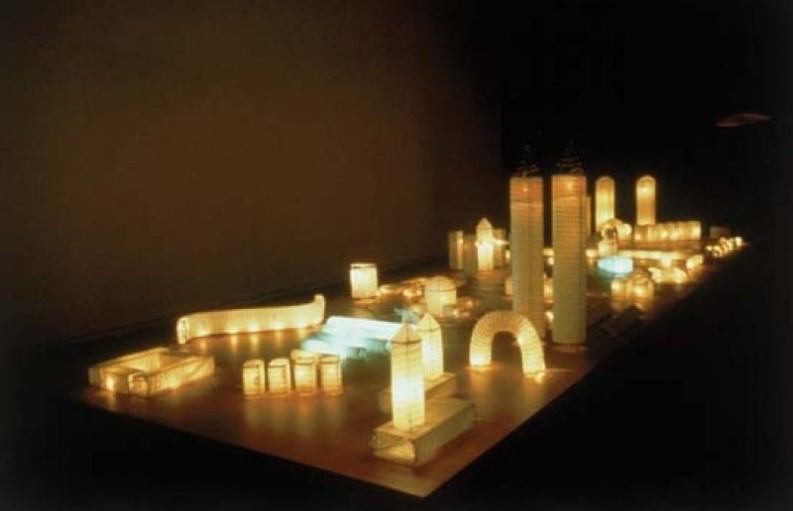

In the 1990’s contemporary artist Carlos Garaicoa addressed the yearning to reconcile the initial revolutionary dreams with its subsequent fractured reality. Taking the viewpoint of an urban planner/architect his early installations envisioned new cities from the architectural remains of a remote, utopian era.

Lombard-Freid Fine Arts. Reproduced in Bomb magazine article by Holly Block

In 1967 the Casas Batista family were able to admire an example of cutting edge Cuban architecture in the form of Vittorio Garrati’s Expo 67 Cuba Pavillion. They had left Cuba the previous year and installed themselves in Ottawa, Canada.

Still homesick, Eddy and Teresita spoke to the Cuban guides and gazed at the symbol of the revolution’s future. Having left an increasingly repressive society, they wondered whether that future would, in fact, ever arrive.