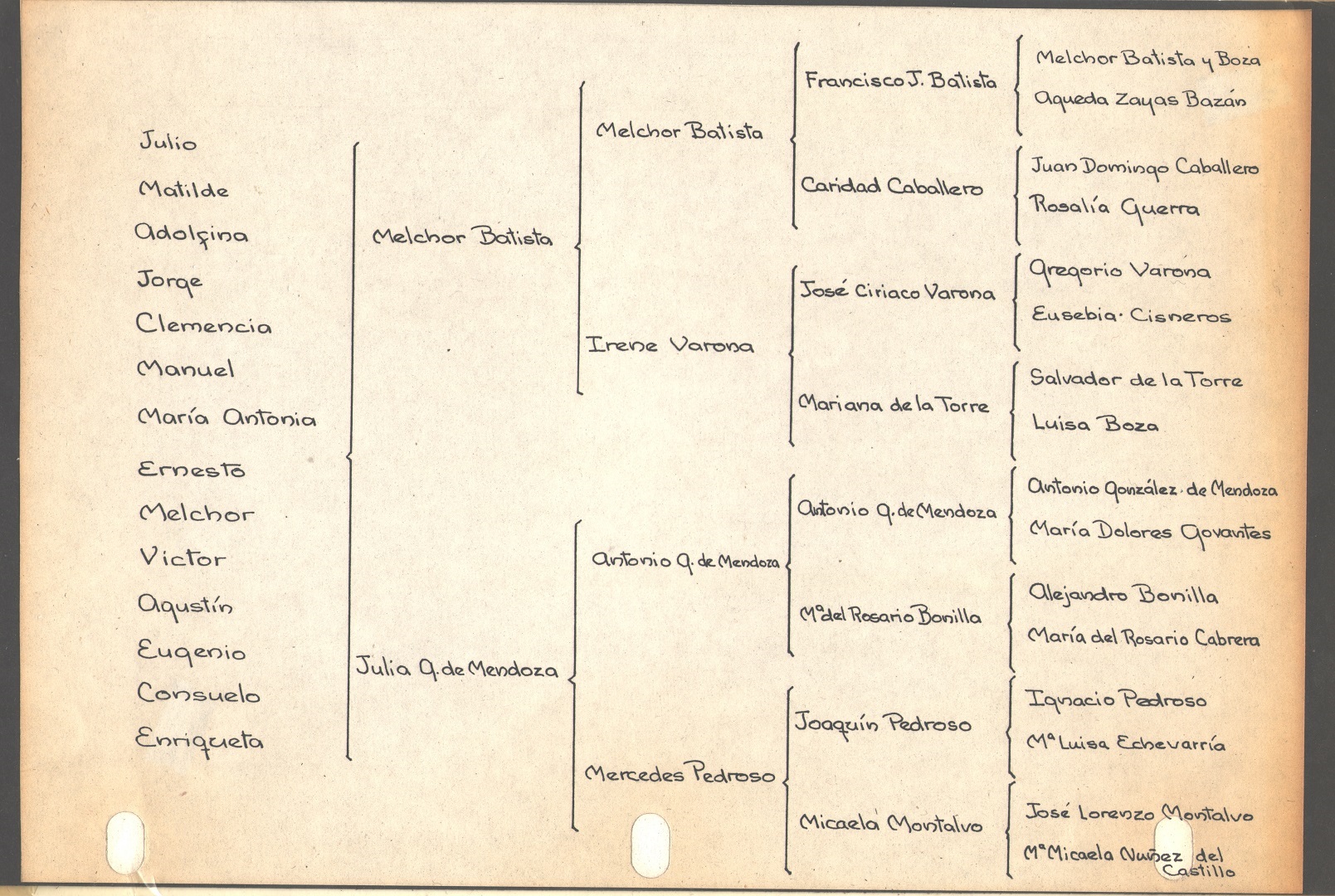

Pedroso – Gonzalez de Mendoza

The first accounts of the family history focus on the rejection of the Pedroso fortune by his great grand daughter in marrying for love rather than consolidating family wealth within the “sugarocracy.”

See Chapter 1 (p.5)

On my 2009 trip to Havana with my father, we found interesting echoes of the colonial economy and partitioned society in today’s tourist-oriented city.

See Chapter 2 (p.22)

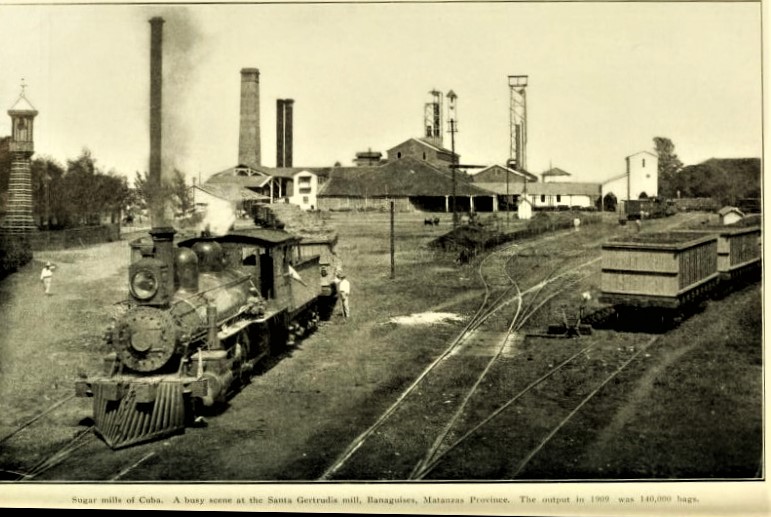

The brothers used the newly invented steam-powered trains and sugar processing machinery along with an a vast number of enslaved African and Chinese workers to amass a fortune in the first half of the century.

Joaquin hoped to arrange the marriage of his daughter, Mercedes “Chea”, to the Forcade family to facilitate the construction of rail and port connected to his sugar mills in Matanzas province. She had other plans. See Chapter 3 (p.43)

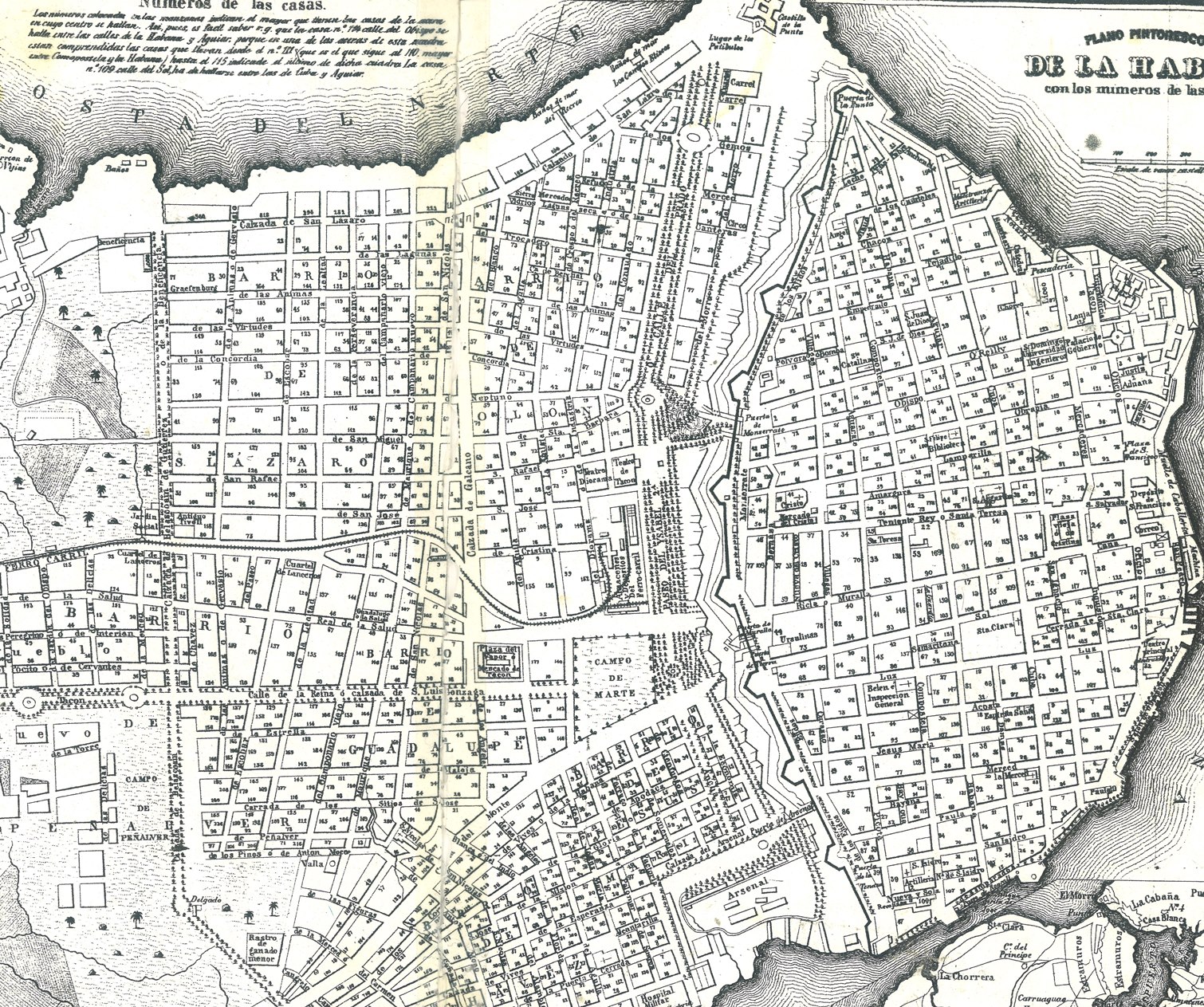

Chea eloped with Antonio Gonzalez de Mendoza in 1855. They first lived with his parents on Salud street outside the city wall.

Her daughter Julia (b.1860) wrote Fechas de Mi Vida a memoir of the essential dates and facts about her family including the places where they lived in Havana. (See Supporting Documents for English translation.)

Julia’s first memory was of the funeral of of her younger sister in which the procession travelled from the family’s first home on San Ignacio street to the Espada cemetery west of the city. For detail view from higher resolution map, click Map of Havana 1853, Wikipedia, accessed 2021

Angry over his daughter’s elopement and the couple’s abolitionist views, Joaquin cut off communication with his daughter and son in law for many years.

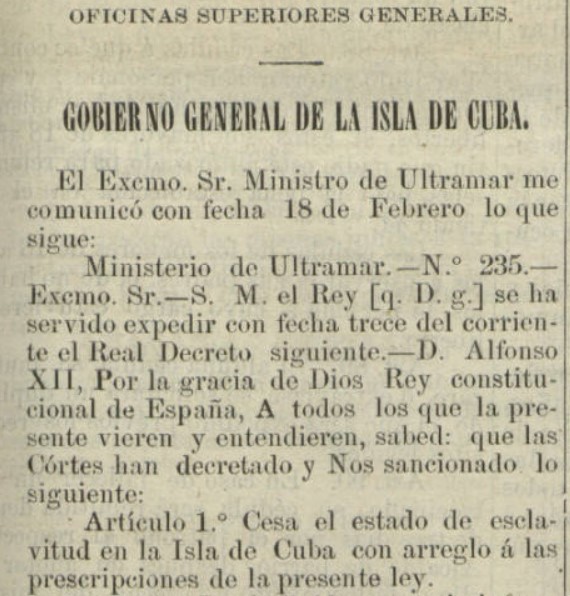

The sugar industry depended on enslaved African men, women and children along with Chinese indentured laborers. Slavery endured in Cuba until 1885, long after it was formally outlawed in most parts of the world.

Joaquin Pedroso owned four sugar cane plantation and mills or “ingenios” the largest of which was Santa Gertrudis in Matanzas province.

Plantation slaves and workers during a break at noon, 1863 cropped view of stereograph, University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection accessed April 9, 2021

Ruins of the Santa Gertrudis slave barracks were inhabited by numerous families at the time of the following research (The Architecture of Nineteenth-Century Cuban Sugar Mills: Creole Power and African Resistance in Late Colonial Cuba Lorena Tezanos Toral: 2015)

These and other female family voices reflect history as it was lived on an intimate scale. They expose such issues ignored in broad-view political and economic histories as the intricacies of power relations within the family, the lasting effects of illnesses and deaths, the importance of religion and education, and the legacy of setbacks and pride through the generations.

Chea made daily visits to the Carmelite convent and church of Santa Teresa de Jesus for mass and to report on her work as part of the “Hijas de Maria” charitable organization.

A strong believer in education, she enrolled her children in a kindergarten style preschool and her daughters in the Sagrado Corazon school in El Cerro.

Cuban women had no role in politics however, through connections and money, many like Chea sought to improve civic life through charities.

Late in life, she took a vow of poverty, dressed simply and cut her hair short. Chapter 3 (p.43)

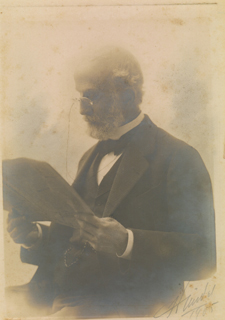

Don Antonio believed that Cuba did not have the democratic foundation for independence after colonial rule. He saw U.S. annexation as the best course for the country.

In 1870, after the outbreak of the first war of independence from Spain (1868-78), Antonio and Chea along with many other “Cuba Libre” exiles left the country. They settled in New York and then lived briefly in Germany before ending up in Madrid. By 1873, they had run out of money and returned to Havana.

At the conclusion of the war, when Cubans were offered limited political freedom by Spain, he was appointed Mayor of Havana. He held office between 1878-9. Chapter 4 (p.61)

Joaquin Pedroso died in 1878. The following year, Antonio and Chea liberated the Santa Gertrudis slaves upon inheriting the sugar mill. Slavery was gradually phased out between 1879 and 1885. See Supporting Documents for Legal Record of Liberation, featured in an early edition of the Gonzalez de Mendoza family book

For Timeline of Events Discussed in Chapters 1 – 4 See Part 1 (pp. 71-4)