Under President Gerardo Machado, the corruption that had plagued earlier administrations was flagrantly practiced and American economic influence was embraced like never before.

In 1928 Machado amended the constitution in order to extend his term six more years. Along with the curbing of civil liberties he began to brutally silence opposition with his personal army of thugs nicknamed la Porra (the Hell). The University of Havana, centre of student-led dissent was shut down in 1930. The tension culminated in a grass-roots revolution in the summer of 1933.

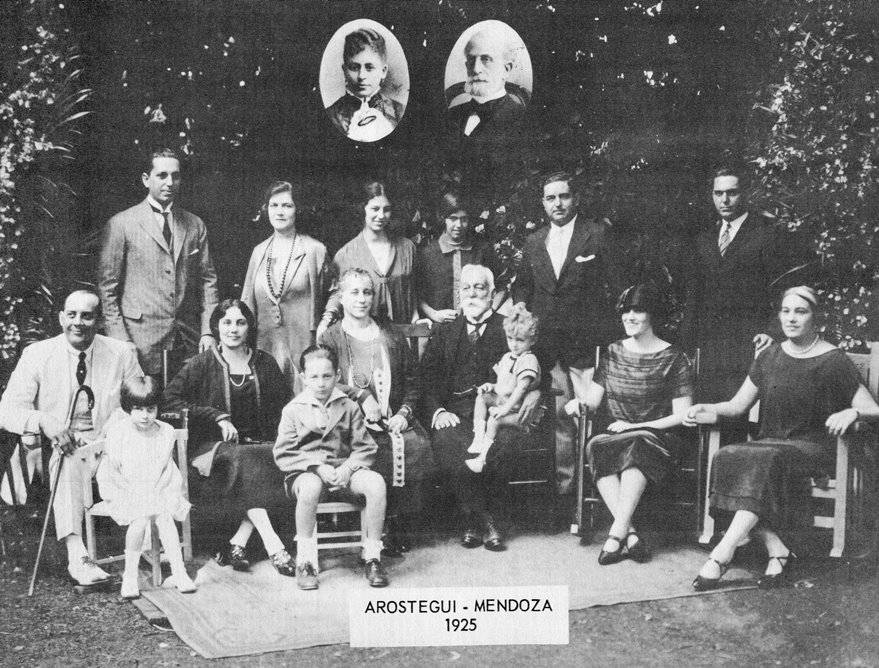

There were contrasting attitudes among the branches of the G. de Mendoza family towards the Machado regime.

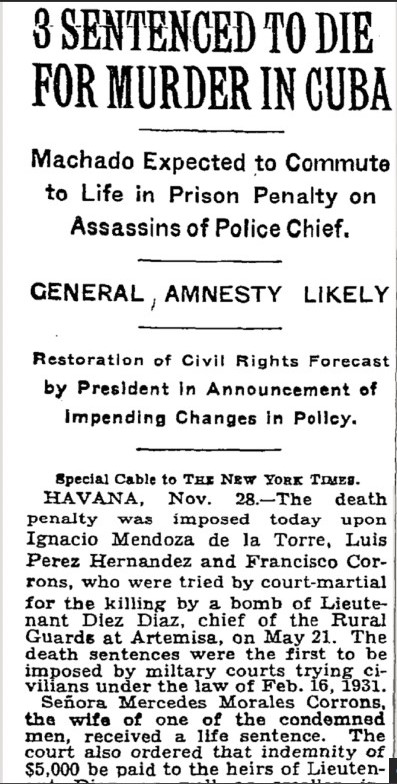

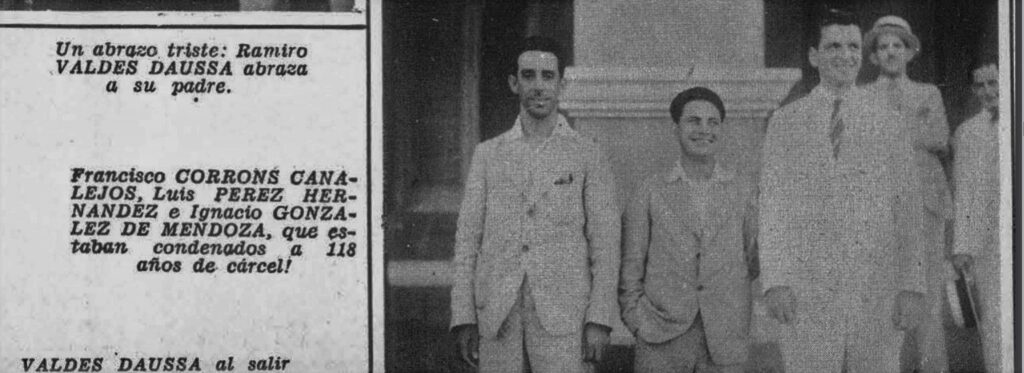

Ramon Mendoza’s son, Ignacio, was part of a Communist student underground organization, Ala Izquierda Estudiantil, that carried out anti-Machado terrorist acts.

On May 20, 1932, Ignacio was implicated in a deadly attack: a letter bomb sent to a police commander that killed him on opening it. Additionally, he was cited as part of a group that planted a bomb on the Quinta Avenida. It was set to explode as Machado’s car passed by on its daily route. This plan was foiled when the president was alerted to the danger as he was leaving the presidential palace. Chapter 13

Upon hearing of Ignacio’s arrest, his mother rushed to defend him, whereupon she too was arrested, imprisoned and sentenced to fourteen years in jail.

Ignacio’s defense team included his aunt Maria Antonia Mendoza’s brother, Congressman Gonzalo Freyre de Andrade. The trial was suspended when a squad of Machado hit men burst into the Freyre home; not being able to identify Gonzalo, they killed him along with his two brothers.

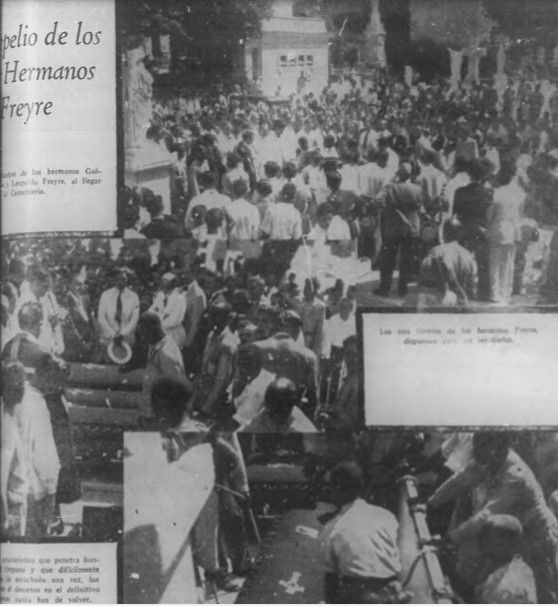

The burial of the Freyre brothers, Colon cemetery, Bohemia, 9 October 1932 p 19

Through the intercessions of highly-placed members of Cuban society along with the family’s influential American network, Mariana was permitted to go into exile in the United States. Ignacio continued in jail until the following summer. He was among a group of student revolutionaries released early in August 1933. Chapter 13

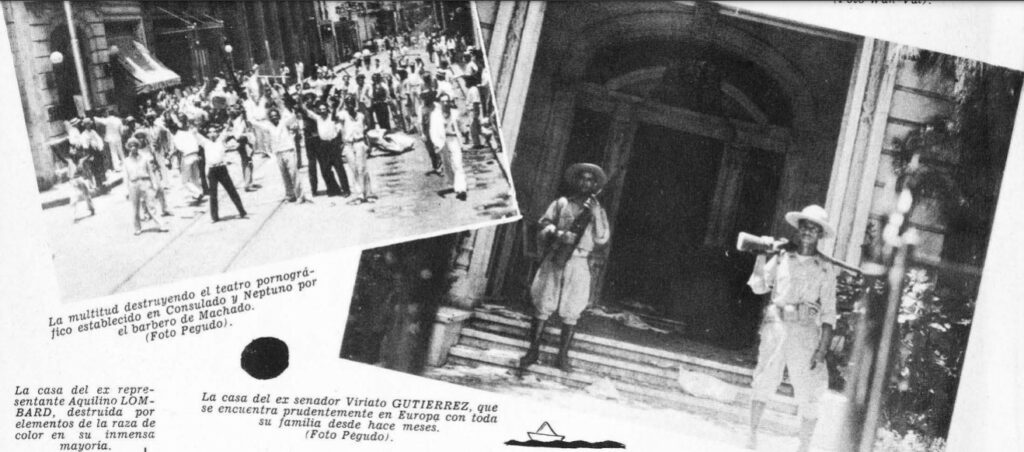

Facing a popular uprising against an American backed leader, Washington sent special envoy Sumner Welles to Havana in May 1933. Welles convinced pro-Machado government members that the U.S. had lost confidence in their leader. Machado was finally convinced to resign and left abruptly by plane. Fulgencio Batista, a sergeant who had won the support of the army, had the Machado loyal officers deprived of their arms.

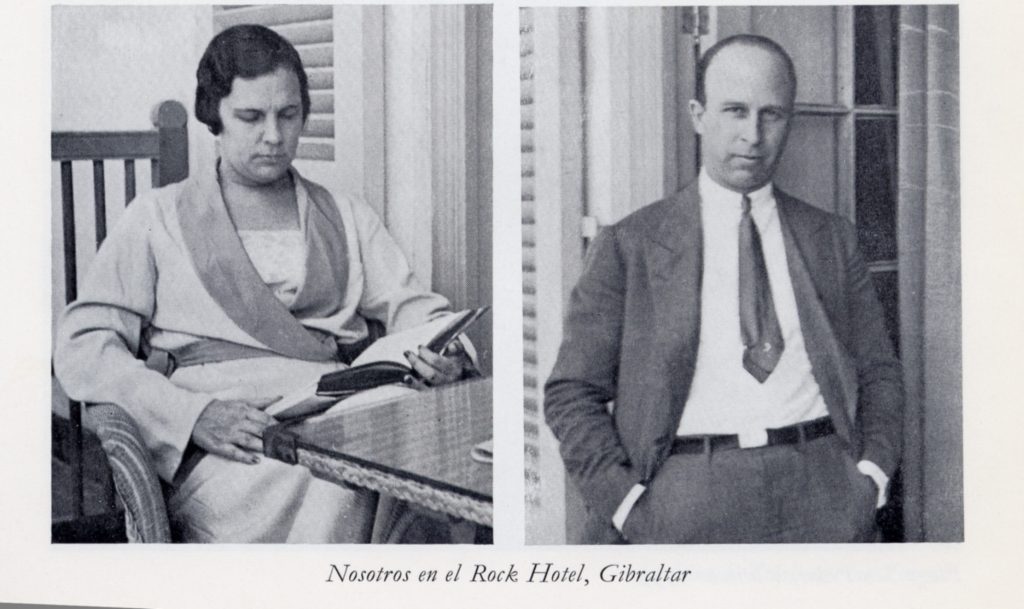

The Batista-Falla-Gutierrez clan heard news of the revolution from where they had taken refuge in Anero, the Falla’s ancestral Spanish village.

What appears obvious is that Machado has fallen and fled the country during which time there has been serious social disorder. I have received several telegrams from home and from the offices of Falla and Claudio informing me that all of our families are safe. We have also been warned that Lala’s (Adelaida’s) home has been looted, although I think that the damage could not have been as serious as others since the papers make no mention of it. I’m assuming that the fall was the result of the military taking affairs into their own hands as it became known that the Americans would not support Machado after the position that Sumner Welles had taken. … Agustin Batista excerpt of letter to his brother Ernesto, August 15, 1933 Cartas de Viaje Chapter 14 p278

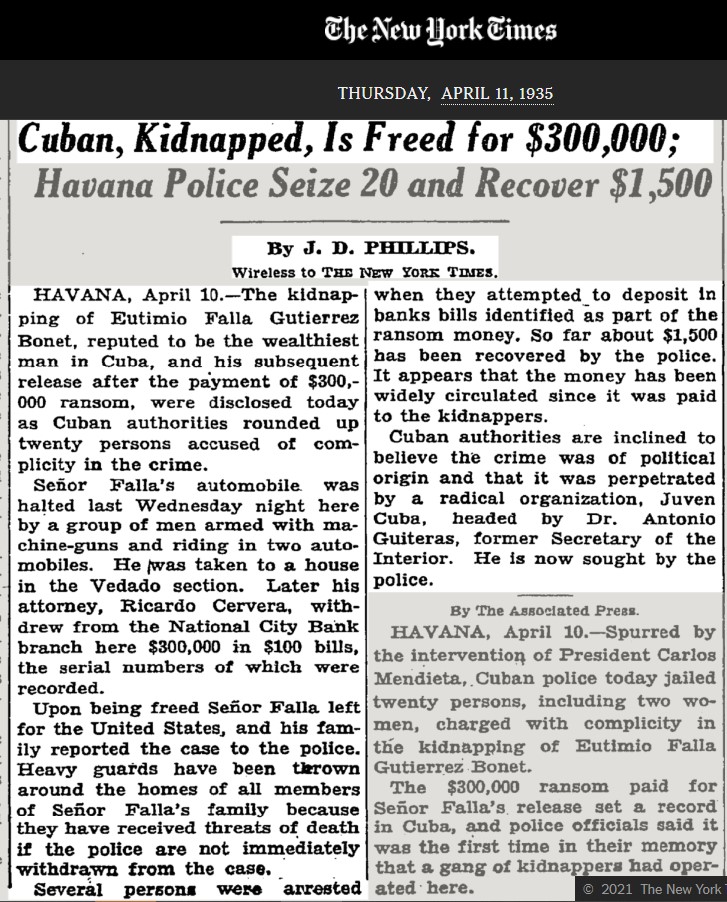

The threat to the Falla family escalated again two years later when Eutimio Falla was kidnapped by a group of revolutionaries led by Antonio Guiteras.

In January 1934 Batista, displeased by the actions of a coalition government that included Guiteras and his Joven Cuba party, shifted his support to Carlos Mendieta. In protest over Batista’s eradication of his government’s reforms, the head of the coalition, Ramon Grau, resigned within the week. Mendieta was now only nominally president; authority rested entirely on Batista, he would, with brief breaks, continue to dominate the country until the next revolution in 1959.

After a year of strikes and protests that culminated in a General Strike in March 1935,

martial law was imposed, the university closed, and political activists were arrested and tortured.

By the spring of that year Guiteras was on the run from police. With a band of women and men he planned to escape the island and set up an off-shore training school for a guerrilla army that would return to topple Batista. In desperate need of money, it was decided to kidnap one of the wealthiest men in Cuba, Eutimio Falla Bonet, the only son of Laureano Falla.

Months later, fleeing the police, Guiteras and his followers were about to sail from Matanzas to Mexico. At the last minute, they were surrounded and the revolutionary leader was killed in a hail of machine-gun fire. In the official narrative of Cuban history Guiteras is hailed as an important figure in the continuing struggle against imperialism.

In later years, during family conversations, there would occasionally be mention of “el secuestro de Eutimio” (Eutimio’s kidnapping). Without speaking directly about the incident, it was a benchmark of the fear experienced when this branch of the Mendoza family became a target for anti-Machado mobs and terrorists. If the bitterness over revolutions’ cost began in that decade, it would grow exponentially thirty years later.

The dominance of the military, its dependence on killing and torture to repress dissent and the corresponding revolutionary attacks against it made violence an ingrained part of Cuban life. In Place offers a glimpse at how the biographical writings of Cuban Americans Louis A. Perez Jr. and Carlos Eire explore this cultural predilection.

The turmoil unleashed by the fall of Machado had not died down with the formation of a provisional government under Carlos Manuel Cespedes. Fulgencio Batista demanded the resignation of the Machado loyalist officers. His aim was to give the impression that he was spearheading a soldiers’ coup to prevent an officer-led overthrow of the post-Machado government.

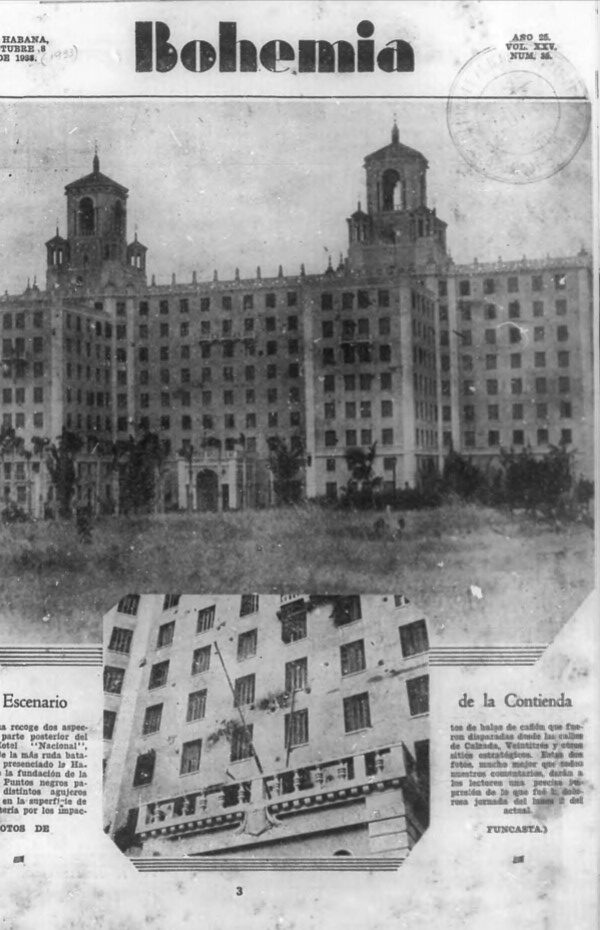

Early in the morning of October 2nd 1933, Batista’s troops positioned tanks and artillery and opened fire aiming at the highest floors of the Hotel Nacional where fleeing Machado loyalist officers had taken refuge awaiting, along with American citizens, to be rescued by ship.

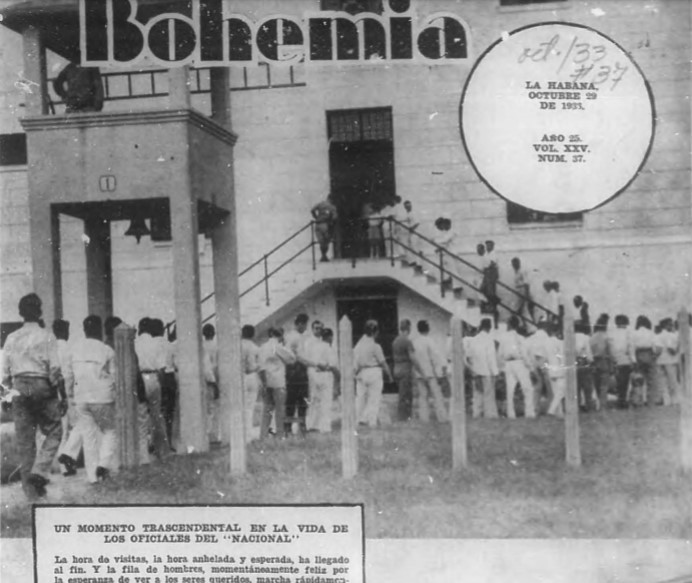

The husband of Nena Arostegui Mendoza, grand daughter of Don Antonio, was among the officers. Arturo Bolivar survived the eight hours of bombardment preceding the officers’ surrender and subsequent imprisonment.

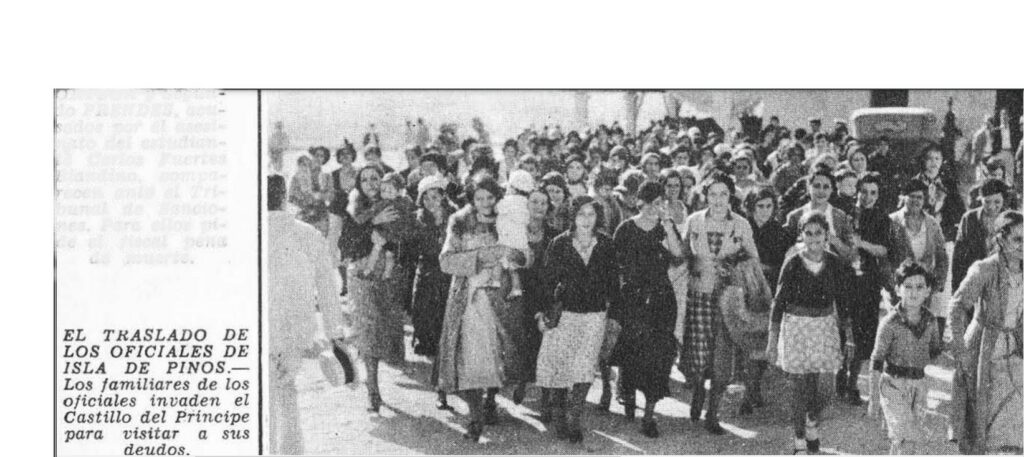

Informed that her husband would shortly be taken to an infamous prison in the Isle of Pines, Nena ran back to her home to pack her car.

Months later, during his transfer back to a Havana prison, she followed to ensure that he would not be killed in transit. A common way to execute prisoners was to claim that they had been shot in an attempted escape.

Although safe, her husband was definitively sidelined in his military career.

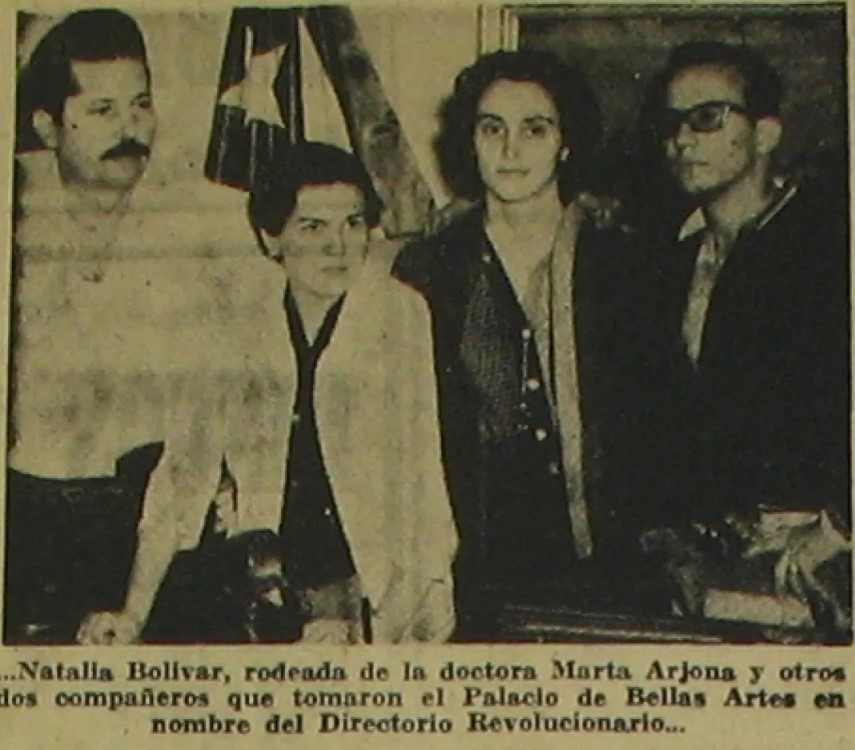

Nena Arostegui and Arturo Bolivar’s daughter Natalia, to expunge what to her must have seemed a grievous political misstep by her father, twenty years later would become a member of an anti-Batista urban underground, helping to lay the groundwork for Castro’s victory. photo caption: “Natalia Bolivar surrounded by Dr. Marta Arjona and others who took control of the national art museum in the name of the ‘Directorio Revolucionario’.”photo: CBC “Natalia Bolivar, Women of the Cuban Revolution” accessed 04/19/21

The political and economic upheavals of the 1930s, hit hard a social class that was used to security. As the target of popular anger or official prosecution, many men lost their jobs or were imprisoned.

Wives became crucial in maintaining the morale of their husbands and

holding families together during depression that came on the heels of the 1933 revolution. In the households of Celia Casas Rodriguez, Nena Bolivar Aróstegui, and Guillermina Batista Villareal, for the family to survive, the role of wife had to be re-interpreted.

Through the life experiences of these women In Place exposes how historical events penetrated deep into the emotional lives of middle class Cuban families. For the three, the prime directive was to give their children an education so that they could maintain a toehold in their social class and never suffer the vulnerability that they themselves had felt in that decade. Chapter 16

Batista Villareal family flanked by Batista brothers Julio and Victor. Although Jorge lost his job overseeing municipal infrastructure projects after Machado’s fall, his brother Agustin hired him to oversee his Sevilla Biltmore Hotel’s physical plant including the very lucrative electric laundromat. Guillermina established a school in 1935 which prospered and in 1937 they moved to a large apartment at the family B y 13 enclave. Jorge’s death that year forced the school’s closure and the widow and her mother to live in a series of hotels.

Guillermina Villareal de Batista and Teresita shortly after the 1937 death of Jorge Batista. His death brought his widow and daughter closer to the extended family but in a position of greater dependence. They first moved in with the unmarried Batistas, Julio, Enriqueta, Consuelo, Victor and Eugenio. Following that arrangement, they moved to a hotel near B y 13 to be able to continue the daily visits to Lola Falla.

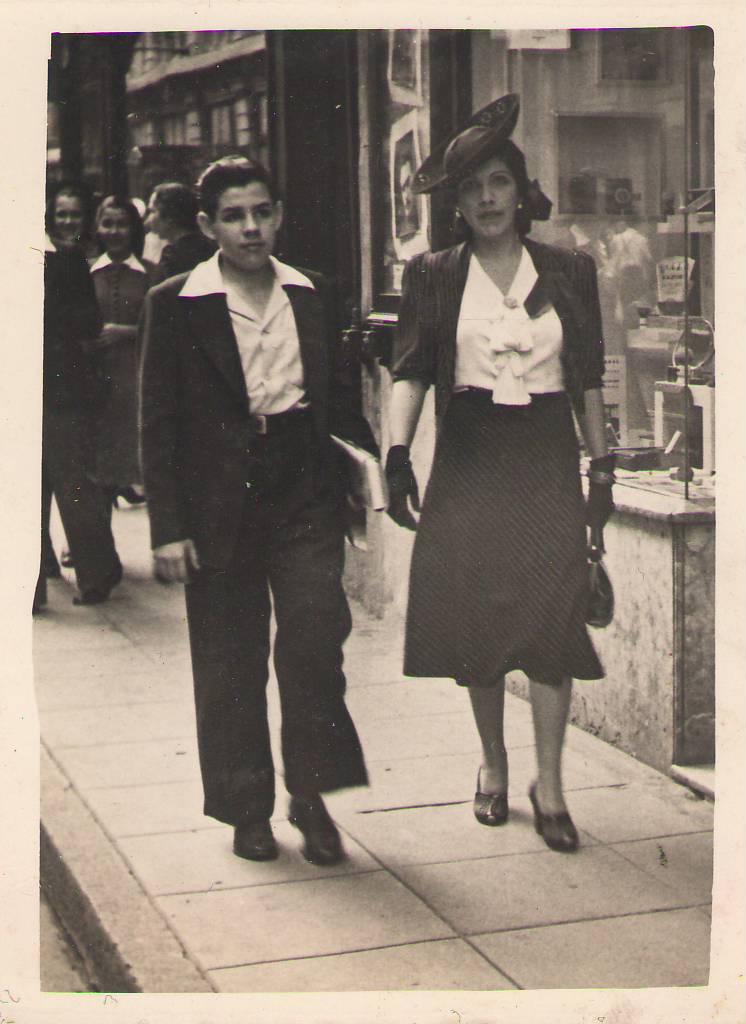

Celia Casas Rodriguez ran a household that included her father who was dying of cancer, her husband who, attacked for representing an party allied with Machado, had lost his medical practice, an aunt and three sons attending the expensive private school, Colegio de la Salle, el Vedado. She was able to supply the family with some money through the rent from property left to her by her grandfather, Ricardo Piloto. In the photo she is accompanied by her last and favorite son, Eddy, whom she made into a confidante and companion.

Nena Arostegui, Guillermina Batista and Celia Rodriguez became wives in the 1920s and suffered the effects of domestic terrorism and political instability along with the loss of a male head of family. Their sons and daughters, born in the years of the depression, would enjoy the relative stability and prosperity of the 1940s but ultimately confront their own challenges to their identity and family solidarity in the 1959 revolution.

For Timeline of Events Discussed in Chapters 13 – 16 See Part V (pp. 324-30)