An island outside time

In 1989 as the Berlin Wall came down, Castro warned of imminent shortages of basic necessities. The Special Period, as it became known, was dominated by the government’s belt-tightening measures to cope with the loss of Soviet economic support. Food rations dwindled to subsistence-level. Alternative systems for accessing basic goods and services such as person-to person bartering developed in the place of the state regulated transactions. Bikes replaced cars on the streets of Havana. Produce gardens were planted in vacant lots. Forced into sudden self reliance Cubans’ perception of the relationship between individual, society and state irrevocably shifted.

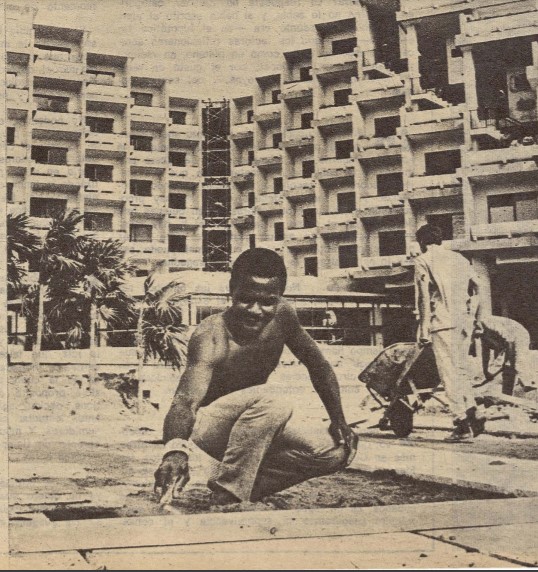

The most successful strategy for immediate cash proved to be the opening up of the country to tourism. The government partnered with Canadian and European companies for the necessary infrastructure and managerial expertise. In 1993, giving a blow to the historical claim of

independence from their capitalist neighbor, the Cuban Congress de-criminalized the American dollar. The state accessed hard currency through their stores where individuals, including Cubans, with dollars could buy otherwise inaccessible goods.

Overnight, Cubans’ marginal existence in the global economy was brought home to them in the dramatic power difference between Cuban pesos and American dollars. The glimpses into restricted resorts, where a vastly superior standard of living prevailed, confirmed the impression. Beyond the lucky ones who could count on overseas money orders, the winners in the new order were those who worked in the tourist industry.

Even as the new levels of private enterprise gave much needed grass-roots momentum to the marketplace, the government became alarmed by its lack of control over the black market. The early Special Period alternated between new freedoms and their sudden and unexplained withdrawal. The official dance of one reform step forward followed, after a period to observe its effect, by another back, became familiar.

In their strategies for producing and disseminating their work, evading censorship and reflecting their society, artists, musicians, writers and other members of creative communities best reveal the problematic of life in contemporary Cuba. With their hard currency contracts they found themselves at the top of Cuban society. They were permitted extended stays outside the country. Moreover, despite living outside the country they retained their status as producers of authentically contemporary Cuban work because they continued to be active, albeit from a distance, in their creative communities on the island. This highlighted the fact that Cuba’s culture was to a significant degree being produced and disseminated from

beyond the country’s borders. Through the work of a number of critics In Place explores examples of Special Period fiction as the product of this historical chapter and cultural dynamic.

The hit feature-length documentary The Buena Vista Social Club (1999), follows

musician/producer Ry Cooder as he reassembles a Havana band to, along with them, revive music that had not been heard for many decades. Implicitly the film treats the ageing musicians as venerable relics, vessels of a culture whose authenticity had long been protected from market corruption.

The movie ushered in a veritable industry, a flood of music, art, photography portraying an island outside history. As Ariana Hernandez Reguant points out, the treatment of Cuba as a static cultural moment endures thanks to the circumstances that came into play in the nineties. “There was to be no official end to Special Period. Without the Soviet Union, the Cuban Revolution survived by turning itself into a new temporal category: the Special Period. Cuba became, for Cubans and foreigners alike, an island outside history lingering in a sort of timeless eternal…”

While Havana residents improvise strategies for adapting to an unchanging reality, outside the island relief from homesickness relies on the city’s unchanging appearance as an important source of memory.

For many years, Google Earth’s Havana map/satellite view, place-markers hyperlink precise geographic locations to street-view photographs. These, taken by private individuals were typically linked to the now defunct photo sharing site, Panoramio. Alongside the “I was here” tourist Havana depictions one could see those of former inhabitants. The latter, shots of humble homes and schools, are identified by former residents as a plea for news from fellow displaced neighbors. The challenge, thrown down by returning Cubans who photograph and post images of street corners, houses or vacant lots, is to collaboratively identify obscure Havana sites as these are depicted online.

Beyond recognizing these as addresses, people enthusiastically write of their memories of family networks, school communities, contemporary neighbors, that these images bring to life. The discussion crosses generations and leave-taking dates, reflecting the reality that Havana’s

streetscapes and buildings are little altered through the decades. It reveals cultural memory in a state of negotiation through remote interpretations of an ordinary place as a historical site. The participatory interpretation of the same site from different locations on the globe and individuals representing different gender, racial and generational experiences of an urban site highlights the Web’s power to reveal and register a complex psycho-geographical landscape, a virtual city composed of numerous subjective memories. In this way, Google Earth facilitates a return, via a community of memory rather than a physical journey.

My research for this family history brought me into the Cuban memory landscape represented in the digitized holdings of as the University of Miami’s Cuban Heritage Collection. Clicking through the online collections of periodicals, paper ephemera, postcards and travel albums revealed the memory work of numerous generations and collectors. I am grateful to have had this rich resource along with my librarian mother’s archive and my father’s oral history as the basis of this diaspora story.