- The Spanish Influx

In the closing decades of the 19th century Cuba was suffering the after-effects of the burnt earth Spanish suppression of nationalist uprisings. The colonial government encouraged Spanish immigrants to come and rebuild the economy. They came in great numbers, reaping the benefits of preferential trading privileges and rock-bottom prices .

In this rags-to-riches category belong my paternal great grandfather, Eduardo Casas, from the port of Sada, in the province of Galicia and Laureano Falla from the Cantabria region also in northern Spain. The Falla and Batista families would become linked in the next generation.

Eduardo Casas, according to family lore, began accumulating his fortune by driving around the war-torn countryside in a horse and buggy with a bag of gold at his feet.

In 1873, the adolescent Laureano Falla, began his apprenticeship with his merchant uncle in Santa Isabel de las Lajas, Las Villas province. The village had grown around the rail depot of a line that ran north from the port of Cienfuegos. During the first war of independence, rebel army groups carried out regular guerrilla attacks on the Spanish supply trains. Lajas needed Spanish merchants to keep its army depot supplied.

In 1879, Laureano Falla moved to Cienfuegos to work as an assistant to another Spaniard whose enterprises included warehouses and livestock. He began to buy land from the failing plantation owners and organize farms to supply produce to the warehouses. From the profit of the tobacco and fruit as well as cattle, he invested in cane fields. Gradually he evolved from managing colonos to owning large tracts of land and sugar mills.

Maria Antonia Bonet married criollo (native born) Julian Villareal and her sister the Spaniard, Laureano Falla. (See Chapter 9 p. 171)

The first couple struggled while the second prospered during wars of independence. The difference in their fortunes was based on the Spanish destruction of criollo properties as well as the advantages the colonial administration granted to incoming Spaniards. Part III Chapter 8

In the 1880s Eduardo Casas met the criollo Ricardo Piloto from Pinar del Rio, the easternmost province of the island known for its premium tobacco. The latter, the son of an immigrant from the Canary Islands, who as such retained his Spanish citizenship privileges, had accumulated a fortune by branching out from his base in tobacco to real estate, and land investments.

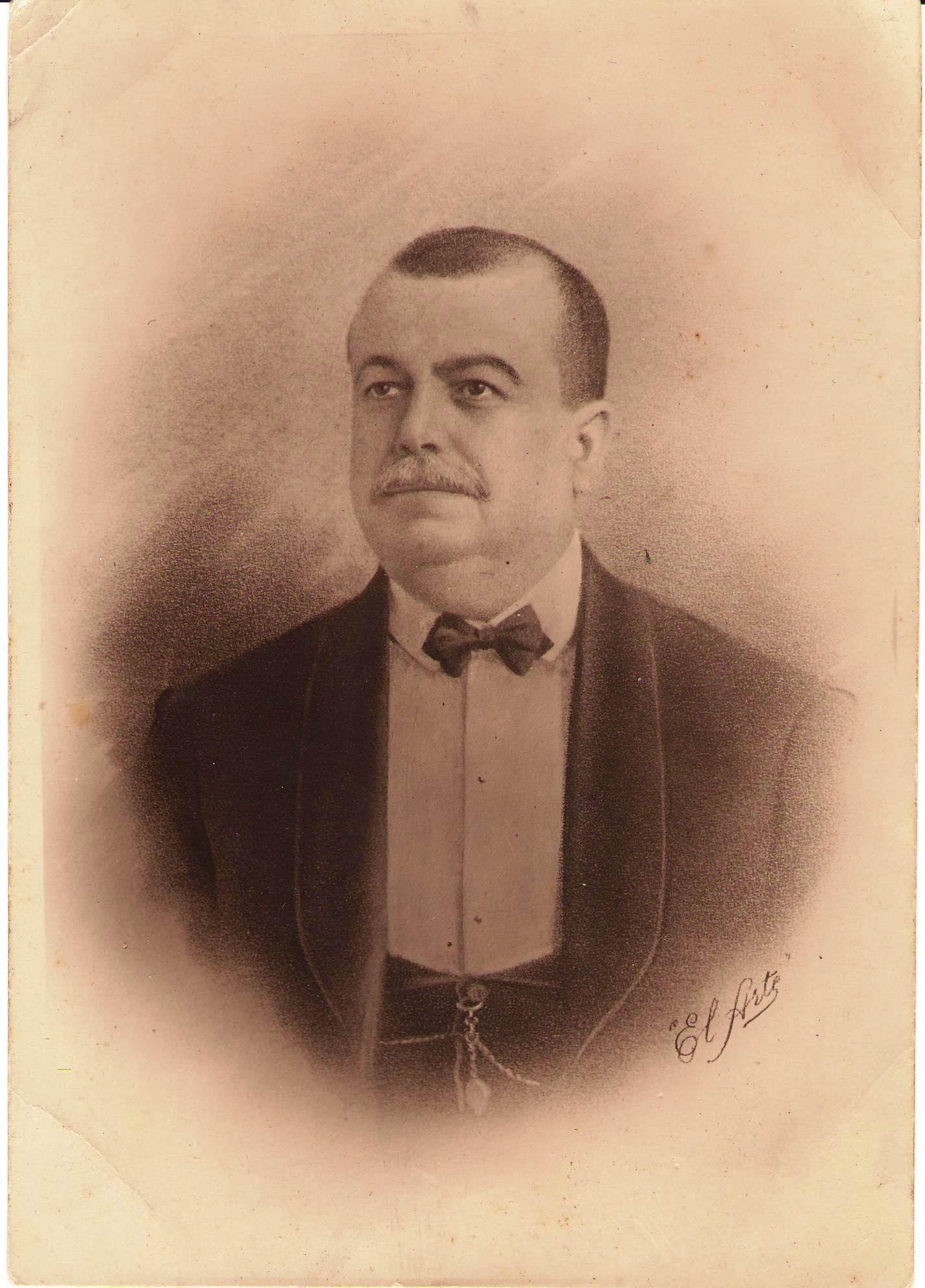

left: Ricardo Piloto

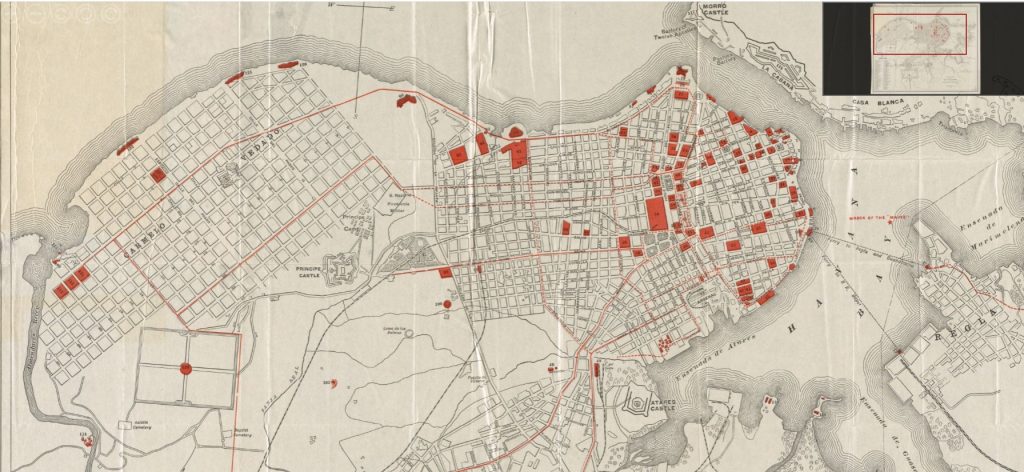

Piloto and Casas settled their families in the capital. Havana was a magnet for the newly wealthy. It was the location of the most prestigious school for sons, the top marriage prospects for daughters, fashionable shopping and the chance to rub shoulders with the best society. Houses in the El Vedado district were designed in the latest Beaux Arts styles to support the cultural and social aspirations of the newcomers to the capital.

The balls, and especially the masked balls held in winter months at the theaters, were the highlight of the social calendar. It was likely in this kind of setting at the close of the war and the beginning of the century that the Piloto sisters met the Rodriguez brothers from Cienfuegos. Eloisa married Saturnino and Maria married Antonio.

Part III Chapter 8

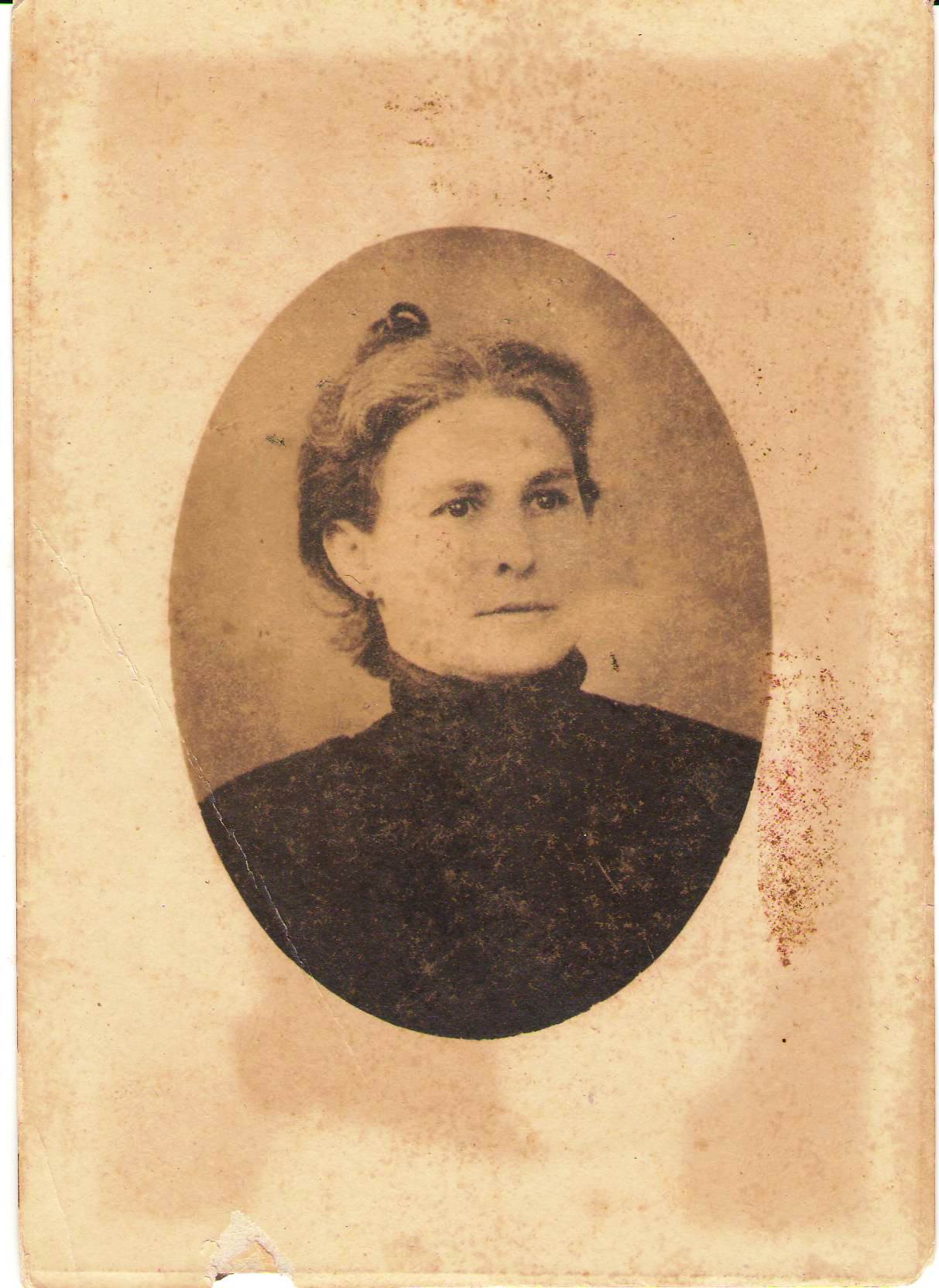

left: Maria Piloto, daughter of Ricardo

The Rodriguez-Piloto marriages were the basis of a less than happy family life in Ricardo Piloto’s El Vedado mansion. According to her daughter, Eloisa’s infatuation with Saturnino Rodriguez evaporated as she became aware that her husband was a rigid, conservative man. Antonio died early in his marriage to Maria. photo: Antonio Rodriguez

The somber mood of the three generation Piloto household was sealed by several deaths. Celia, the third Piloto daughter died as a teenager, and Eloisa as a young mother in 1913. The latter left two children one of which was my paternal grandmother, Celia Maria, “Celia” Rodriguez, seen in the photo.

Chapter 8 p. 164

The two sides of my family, Casas Rodriguez and Villareal Bonet reflected the new top-rung social mix of the island: criollo, peninsular, old money and new money, urban and provincial.

The central provinces of Las Villas, Matanzas and Camaguey were the focus of the final war of independence.

Children of reconcentrados, Library of Congress. cropped view of stereograph

Guillermina Villareal Bonet born in 1895 in Santa Isabel de las Lajas, Las Villas, retained memories of the widespread suffering, describing how the dying would take refuge under the portals of her home. Her own family, meanwhile, had very little. See Recuerdos, translation

We were related to very distinguished families in the village, in the province and it was impossible for her to forget this so that on top of our poverty we had to constantly struggle to maintain appearances.

(Guillermina speaking of her mother)

It was largely through food supplied by her sister Lola Falla, in Cienfuegos, and the assistance of loyal liberated servants that the Villareal Bonet family survived the worst days of the war. The other Bonet sister, Otilia, living in Sagua by the turn of the century, established a base there for Antonia and her children by helping to prepare the eldest, Matilde, to teach.

The family followed, leaving the Lajas house and lands to tenants. Teaching, one of the few professions open to women, was to become the family life-line. Chapter 9

Between 1900 and 1910 two of her sisters, first Matilde, the eldest, and then, when she married, the middle sister Hortensia, studied, passed exams and were appointed to a teaching position so becoming the family breadwinner. The youngest, Guillermina began her teaching career in 1914.

It was during this period in Sagua la Grande, when she was five to nineteen years old, that her world view was formed through close observation of town, school and domestic life.

See Supporting Documents: Guillermina Villareal Recuerdos Translation

Guillermina’s training was influenced by the educational techniques and values of the American reformers. She fell in love with school through the Montessori style progressive education she received from occupation teachers before leaving Santa Isabel de las Lajas.

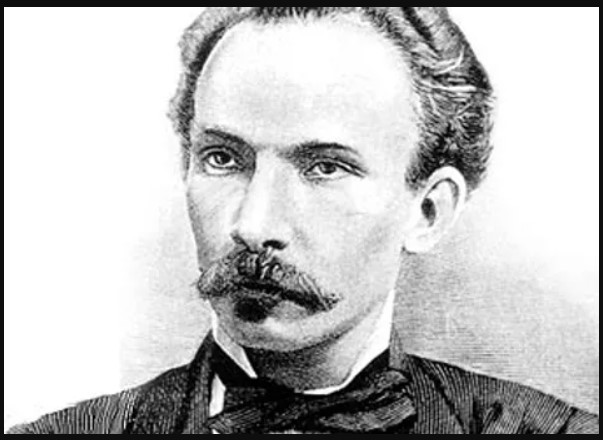

Like many Cubans, she valued universal education as a cornerstone of independence. This was a central tenet of nationalist martyr, reformer and writer Jose Martí whose bust is featured in every Cuban school. left: Revista Agrafos: Jose Marti y La Edad de Oro

- The American Influx

When war was declared between Spain and the United States in 1898, some of the Gonzalez de Mendoza family members went into exile in the U.S. while others took refuge in Santa Gertrudis. By 1902 they had regrouped in Havana to celebrate the new republic.

Through contemporary sources, In Place explores the American occupation as it “cleaned up” Havana with civic infrastructure projects and social reforms. It highlights the roots of the cultural intertwining of Cubans with “El Norte” and highlights the American influence on the Gonzalez de Mendoza family fortunes in during the first decades of the century.

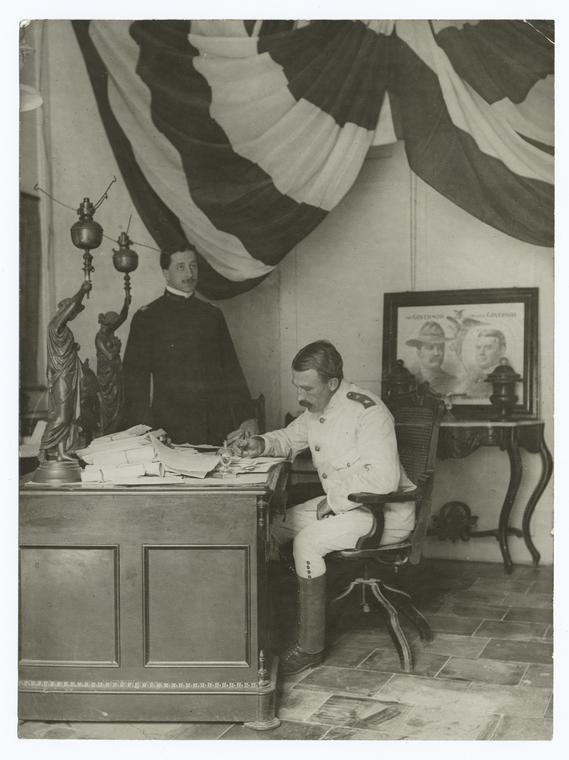

Ramon joined the American army, taking part in the decisive battle in Santiago as an assistant to General Lawton. This photo features the military governor Leonard Wood and an unidentified officer, likely Ramon Gonzalez de Mendoza. View photo within digital collection: New York Public Library

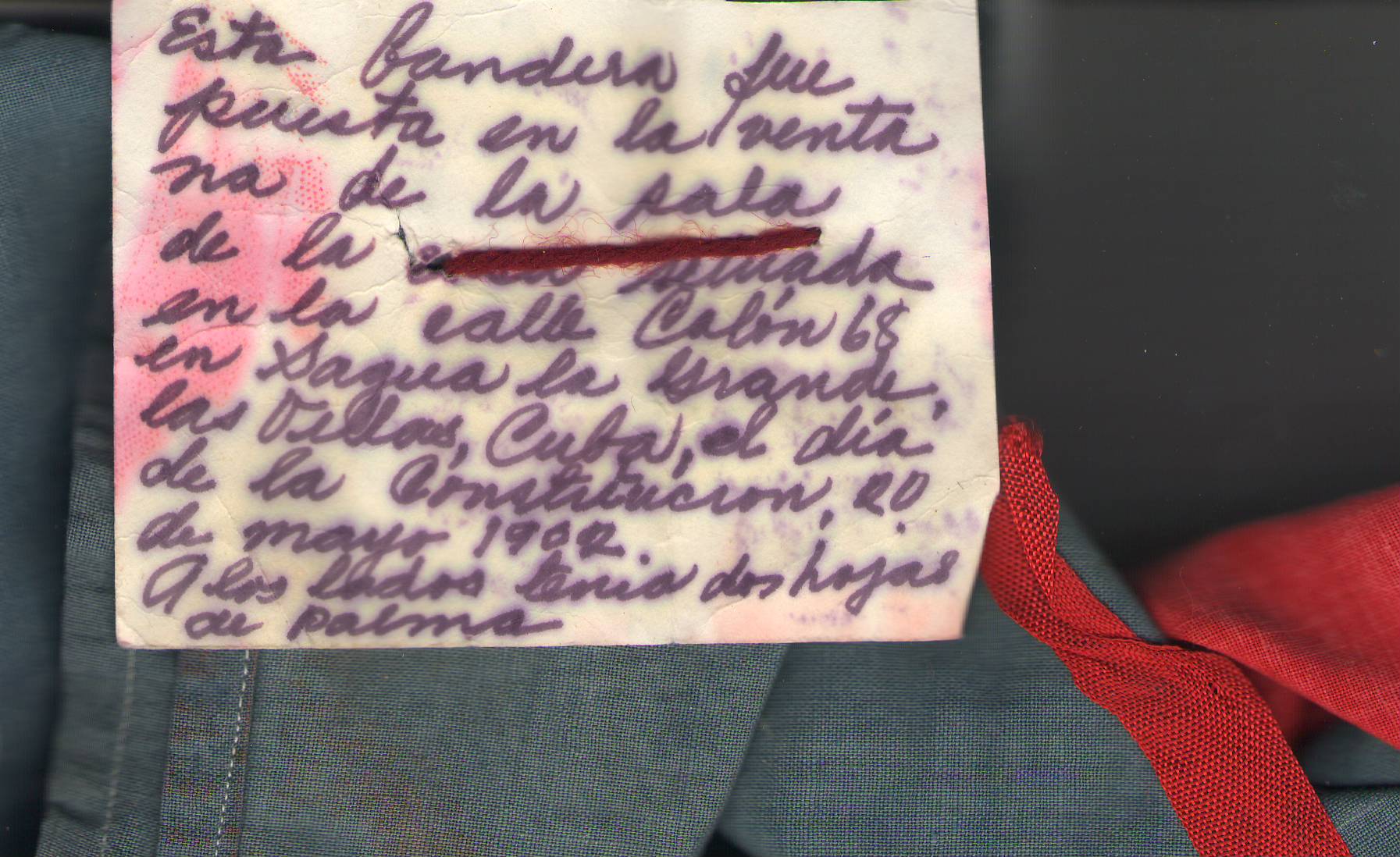

On May 20, 1902, Wood transferred power to the new republic. Two years later, the Americans were back for a further period in power as a result of a political crisis. They would return periodically, under the terms of the Platt Amendment, purportedly to stabilize government and more pointedly to protect American investments.

For Timeline of Events Discussed in Part III Chapters 8-10 See Part III (pp. 212-217)